This is the

smartphone version of this web page. For the desktop version

click here.

Kynouría:

traces of the past

Jaap-Jan

Flinterman

Some incomplete

impressions of my favourite

Greek destination, based on quite a few holidays spent there since 2008

and on

archaeological and historical publications about the region: the east

coast of

the Peloponnese south of the Argolída. Kynouría is sandwiched between

the

Argolic Gulf and Mount Párnonas: the mountains and the sea are never

far away.

What

can you expect from this web page? It is the work of a retired lecturer

in Ancient History, but Greece does not cease to fascinate him when

Antiquity ends. It reflects the limitations of his own sightseeing and

reading, and is emphatically not a complete guide to the region. The

content consists of some geography and history of Kynouría, as well as

descriptions of a number of sights. In principle, we

follow the

coastline from north (Ástros) to south (Leonídio). Occasionally we

leave the

coastal strip for visits to the hinterland. The remains of the villa of

the

second-century plutocrat Herodes Atticus near Ástros are covered quite

extensively, as is the Archaeological Museum in that town. Furthermore,

the webpage offers shorter descriptions with some photos of a small

selection from the region's numerous monasteries; of the castle of

Parálio

Ástros; and of remains of ancient settlements and sanctuaries. A

relatively large amount of space is devoted to the archaeological site

of Ellinikó Astrous - Teichió (Eua), which I have visited on several

occasions. In

South

Kynouría, Leonídio and its hinterland, we tour monuments recalling the

Greek civil war: a historical episode to which much attention is paid

on

Greek-language web pages on the region's history. The itinerary

concludes with

a visit to the mountain villages of Prastós, Plátanos and

Kastánitsa and

to the plateau north of Mount Párnonas. A more detailed table of

contents, with

links to the various pieces of information and sights, can be found

below. To

weblogs and sites of people from the region (often with brilliant

photos, much

better than those of my own making) I have diligently linked.

The information on this web page is

accounted for in the form of a list

of literature and web pages

consulted, in many cases with a brief indication of what

was taken from a publication. Where

the text

of the

web page attributes a fact or opinion to an author and/or mentions a

title, the

details can be found in this bibliography. If you

have problems finding a title, please consult the desktop version (link at the top of this page). There, the bibliography is

regularly linked from the text. In this smartphone version, an excess

of links would not be very user-friendly. Therefore, there are no such

links here.

I

will not give a complete key to the bibliography, but

an exception should be made to highlight the standard Greek-language

monograph on Kynouría in Antiquity by Panayiotis

V. Faklaris (1990). It is true that

the book was published 35 years ago. Archaeology is hardly a stagnant

discipline, and new finds or new insights inevitably lead to

established beliefs being challenged. But Faklaris's work is of

enduring importance because of his meticulous reporting of the

archaeological data available when the book was written, in the

1980s, and because of his unrivalled knowledge of the region. I have

not always referred to Αρχαία

Κυνουρία

(this is not a scholarly publication, after all), but the reader of

what follows should assume that I have benefited from Faklaris's work

even

where

it is not mentioned.

This

web page reflects a personal predilection, but I would not have been

able to pursue it without the help of others. I first visited Kynouría

in 1973, when I was eighteen, during a walking tour of Arkadía and

Lakonía led by Herman Hissink (1915-2011: Ας είναι ελαφρύ το χώμα που

τον σκεπάζει), then a teacher of Dutch at the Christelijk Gymnasium

Sorghvliet in The Hague and an incomparable explorer of Greece. One of

my vivid memories of this trip is how often we got lost. That never

happened when Wendy Copage was my guide during two walking holidays in

2022 and 2023. Thanks to her, I walked trails and visited places that

would have remained inaccessible without her expert help. Last but not

least, my wife Susanne and son Simon have put up with my sometimes

hard-to-follow enthusiasm during ten family holidays since 2008.

The transliteration of Modern Greek follows, by and large, the rules of

the journal Pharos

of the Netherlands Institute at Athens ('Instructions to authors

2019'). These are in most cases in accordance with the rules of the Journal of Modern Greek Studies,

with a few exceptions, e.g. γ > y before ε, ει, η,

ι, υ. In a deviation from the rules of Pharos, I

transliterated υ (ypsilon)

as y: 'Tyrós', not 'Tirós'. For details click here. As for Ancient

Greek, personal names have been latinized (Thucydides, Polybius) or

Anglicized (Lucian). In the case of ancient toponyms, I have

generally stuck closer to the original word image (Anthene, Argos,

Polichne, Prasiai, Tyros), unless there is a common modern version of

the name in

English (Athens, Corinth).

Unless

indicated otherwise, the

photos on this web page were made by Jaap-Jan Flinterman. You are

allowed to download, copy,

re-format and redistribute my photos. For conditions, see the desktop

version of this web page (link at the top of this page). There, in most

cases, the

original large-size file is linked to the downsized version on display.

Comments and corrections are welcome. Please send me a message.

Published online on

5 January 2025. Last update or correction: 12 November 2025.

Table

of contents

Kynouría:

some

geography

The region of Kynouría (open

link in

Google Earth),

part of the regional unit of Arkadía, stretches along the Aegean

Sea or, to be more precise, the Argolic Gulf. The coast consists of a

series of

bays, separated by capes. The beaches are generally of small pebbles;

only at

Ástros is there a sandy beach. As the crow flies, the northernmost and

southernmost points are some 55 km apart, but the distance along the

winding

coastal road is considerably longer, some 100 km. To the north, the

region

borders the regional unit of Argolída; the natural border here is

formed

by the

spurs of the Parthénio massif, especially the Závitsa; to the south,

where

Kynouría borders the regional unit of Lakonía, the border is marked by

the

Madára

massif. The narrow coastal strip widens into modest plains in two

places: in

the north at Ástros and Áyios Andréas, where the Tános and Vrasiátis

rivers, and in the south at Leonídio, where the Dafnónas flows into the

Argolic

Gulf.

The coast at Paralía

Tyroú - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

The coast at Paralía

Tyroú - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

The coastal strip and plains are

suitable for olive and fruit trees, and near the larger settlements

there is

also horticulture. In the nineteenth century (and probably also

before), market

garden products from Leonídio were exported by caique to Constantinople

and

Smyrna and even to Alexandria. The hinterland of the coastal strip is

formed by

a plateau of between 650 and 800 metres altitude, where winter cereals

used to

be grown and where small livestock is kept; maize,

pulses and potatoes are also grown there, and there is some viticulture

and

some tree cultivation (apples, pears, chestnuts, nuts). Behind it rise

the

forested slopes of Mount Párnonas; the highest peak is Megáli Toúrla

(1934

metres). Mount Párnonas forms the western border of Kynouría; as the

crow

flies, the distance between the coast and the central massif is about

20 km.

Mount Párnonas seen

from the Vrasiátis riverbed - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Mount Párnonas seen

from the Vrasiátis riverbed - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

The traditional dialect of the region

around Tyrós and Leonídio, Tsakonian, differs so much from standard

modern

Greek that it seems to be practically unintelligible to Greeks from

outside the

Eastern Peloponnese. According to those who cherish Tsakonian, it goes

back to

the Doric dialect of the Greek language spoken by the ancient Spartans.

Modern linguists take this claim seriously, see Liosis 2013.

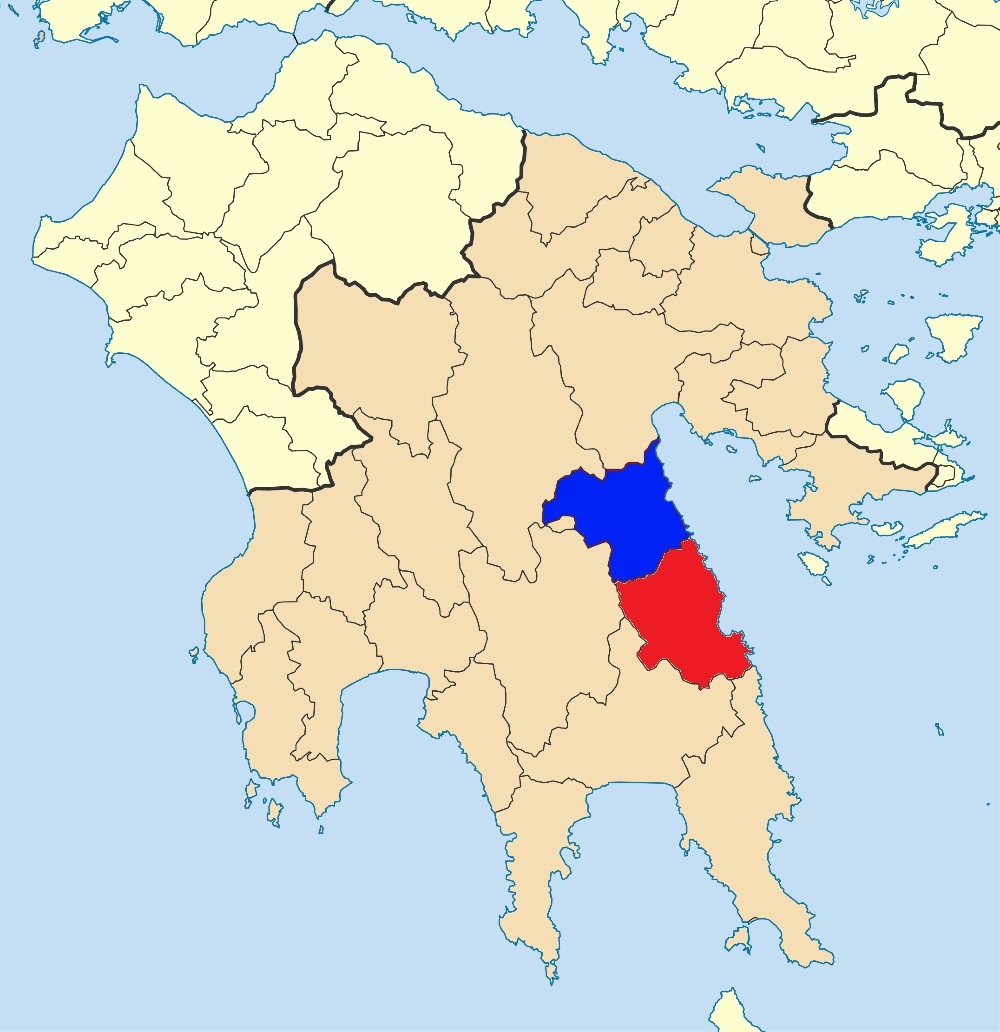

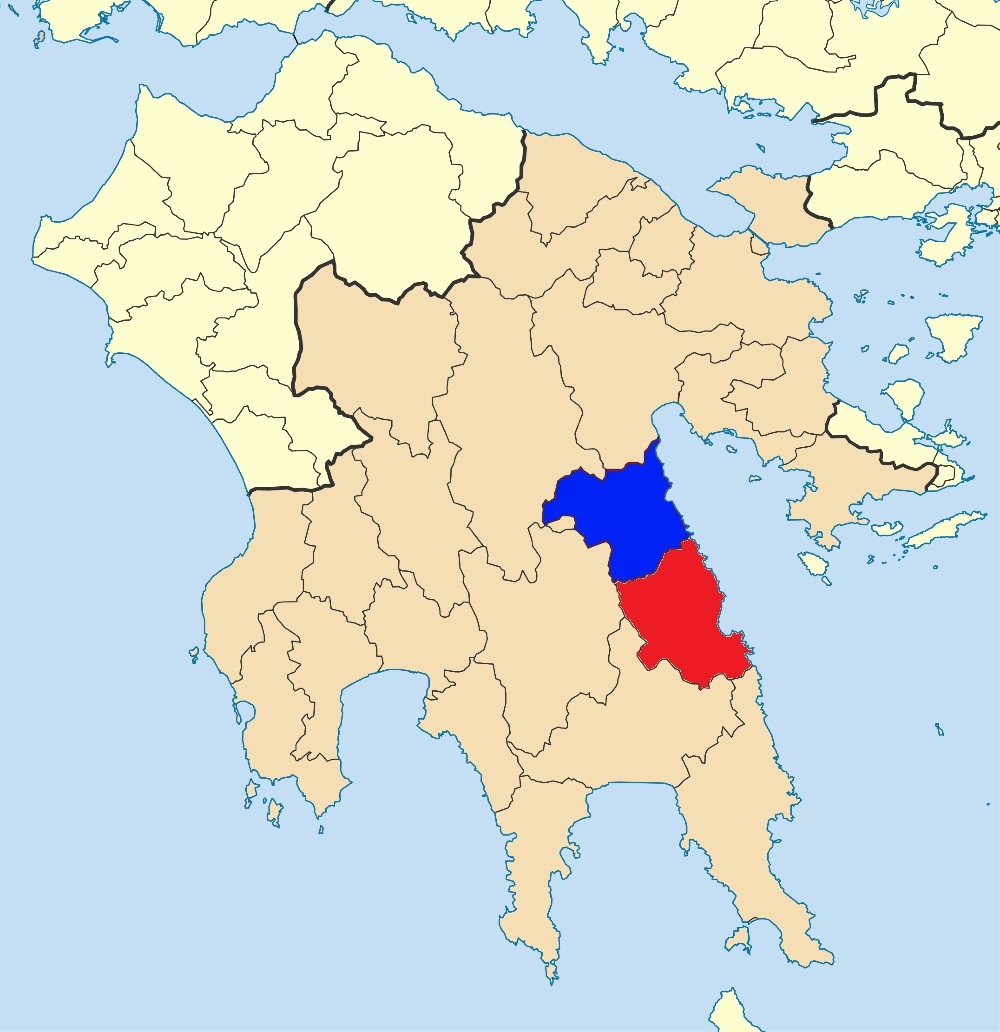

On this

map, the area where Tsakonian was still spoken in the late

19th century is

coloured blue.

"Our

language is

Tsakonian. Ask us to speak it with you."

"Our

language is

Tsakonian. Ask us to speak it with you."

Bilingual sign in

Leonídio - Photo: Wikimedia Commons (Miko), GNU

Kynouría is sparsely populated: from

the middle of the 19th century until the eve of the second world war,

the population

grew from about 25,000 to almost 32,000 souls, before shrinking to

about 20,000

souls at present (in the early 2020s). At the time of the 2021 census,

20,654 people lived in

Kynouría, 11,836 in Vóreia Kynouría (North Kynouría) and 8818 in Nótia

Kynouría

(South Kynouría). North and South Kynouría are the two municipalities

into

which the region has been divided since the 2011 municipal

reorganisation;

Ástros is the main settlement in the north and Leonídio in the south.

During

the summer months, many Greeks who have moved to the city or emigrated

return

to their village of origin. Because of this, and because of domestic

tourism,

the population of Kynouría increases considerably during the summer.

North Kynouría (blue) and South Kynouría (red) - Map: Wikimedia Commons, Pitichinacchio (GNU), adapted

North Kynouría (blue) and South Kynouría (red) - Map: Wikimedia Commons, Pitichinacchio (GNU), adapted

In 1958, Henrik Scholte wrote in his

Dutch-language Gids

voor Griekenland about the east coast of the

Peloponnese south of the Argolída: 'For the length of several hundred

kilometres and very deep into the land, the Peloponnesian coast is

virtually

uninhabited and uninhabitable. (...) Only the tourist, who sails around

the

Peloponnese by liner, occasionally catches a glimpse of this coast,

where the

1,200-metre-high mountains come anxiously close to the sea.' That was

not

devoid of exaggeration even in the 1950s, and since then the area has

been

reasonably opened up by motorways. But it is true that to this day

Kynouría is

devoid of most of the blessings of mass tourism.

Kynouría

in and after

Antiquity

A history of Kynouría worthy of the

name can hardly be written; our information is too fragmentary for

that. As a

rule, Kynouría appears in our sources only when the 'greater'

Greek history

happens to visit the area. Long periods for which information is

totally

lacking alternate with short episodes with a high information density.

In Antiquity, Kynouría was home to two 'city-states' (poleis)

of some significance,

Thyréa (whose core area was the region around Ástros and Áyios Andréas)

and

Prasiaí (the region around Leonídio and Tyrós). There were several

settlements in each of the two territories, the location of which poses

no

small problem for archaeologists and historians: the ancient topography

of Kynouría is, according

to Graham Shipley (1993),

'fraught with debates and difficulties', so that 'attempts

to identify named sites have led to an almost infinite variety of

reconstructions.' The difficulties mainly concern the northern part of

the

region, the Thyreátis. Several settlements are mentioned in literary

sources

from Antiquity, for example in the works of historians and geographers.

But the

place indications in these literary sources are not always accurate,

and

inscriptions that could give a definitive answer have hardly been

found. In

short, the identification of quite a few archaeological sites is

disputed, and

the scholarly debate on the historical geography of the Thyreátis has

been described

as 'a game of musical chairs'.

Territory of Sparta in the classical period - Map:

Wikimedia Commons (Marsyas), CC BY-SA 3.0

Territory of Sparta in the classical period - Map:

Wikimedia Commons (Marsyas), CC BY-SA 3.0

Only from the Archaic period onwards

do we gain some insight into the position of Kynouría in the context of

relations between the larger poleis

on the Peloponnese. (Nigel Copage's website Archaeological

Sites of the Peloponnese

has concise descriptions and excellent photos of what remains of the

major historical centres of power in the Peloponnese.) The southern

part of Kynouria, the region around

Leonídio and Tyrós, was probably taken over by the Spartans in the

decades around 600 BC. [Lanérès

& Grigorakakis 2015 with my bibliographical note] Now

they turned their

eager eyes

to the Thyreátis, which until then had been part of the territory of

Argos. Here is

what happened, if we are to believe the historian Herodotus (Herodotus

1.82;

cf. Pausanias 2.38.5):

It chanced, however, that

the Spartans were

themselves just at this time [547 BC] engaged in a quarrel with the

Argives about a

place called Thyrea, which was within the limits of Argolis, but had

been

seized on by the Lacedaemonians [= Spartans]. (...) The Argives

collected

troops to resist the seizure of Thyrea, but before any battle was

fought, the

two parties came to terms, and it was agreed that three hundred

Spartans and

three hundred Argives should meet and fight for the place, which should

belong to

the nation with whom the victory rested. It was stipulated also that

the other

troops on each side should return home to their respective countries,

and not

remain to witness the combat, as there was danger, if the armies

stayed, that

either the one or the other, on seeing their countrymen undergoing

defeat,

might hasten to their assistance. These terms being agreed on, the two

armies

marched off, leaving three hundred picked men on each side to fight for

the

territory.

Battle

between heavy infantrymen, so-called hoplites - Proto-Corinthian Olpe,

c. 640 BC - Photo: Wikimedia Commons (ArchaiOptix), CC-BY-SA 4.0

(clipped)

Battle

between heavy infantrymen, so-called hoplites - Proto-Corinthian Olpe,

c. 640 BC - Photo: Wikimedia Commons (ArchaiOptix), CC-BY-SA 4.0

(clipped)

The battle began, and so equal

were the combatants, that at the

close of the day, when night put a stop to the fight, of the whole six

hundred

only three men remained alive, two Argives, Alcanor and Chromius, and a

single

Spartan, Othryadas. The two Argives, regarding themselves as the

victors,

hurried to Argos, Othryadas, the Spartan, remained upon the field, and,

stripping the bodies of the Argives who had fallen, carried their

armour to the

Spartan camp. Next day the two armies returned to learn the result. At

first they

disputed, both parties claiming the victory, the one, because they had

the

greater number of survivors; the other because their man remained on

the field,

and stripped the bodies of the slain, whereas the two men of the other

side ran

away; but at last they fell from words to blows, and a battle was

fought, in which

both parties suffered great loss, but at the end the Lacedaemonians

gained the

victory. Upon this the Argives, who up to that time had worn their hair

long, cut

it off close, and made a law, to which they attached a curse, binding

themselves

never more to let their hair grow, and never to allow their women to

wear gold until

they should recover Thyrea. At the same time the Lacedaemonians made a

law the

very reverse of this, namely, to wear their hair long, though they had

always

before cut it close. Othryadas himself, it is said, the sole survivor

of the

three hundred, prevented by a sense of shame from returning to Sparta

after all

his comrades had fallen, laid violent hands upon himself in Thyrea.

[Translation: George Rawlinson, London 1858]

Kynouría as a whole was thus part of

Spartan territory since the 6th century BC. Later generations preserved

the

memory of the heroism of the Argives and Spartans of the sixth century.

Lucian,

a satirist of the 2nd century AD, returns to it repeatedly; in his

view, the

sacrifice of so many human lives for a border dispute is the height of

folly.

In one of Lucian's writings, the protagonist reports on a trip to

heaven he

recently made. During that trip, he had ample opportunity to marvel at

the

futility of all human ambitions (Lucian, Icaromenippus

18; cf. Charon

24; Rhetorum praeceptor 18):

And when I looked at the

Peloponnese and caught sight of Kynouria, I

noted what a tiny region, no bigger in any way than a lentil,

had caused so many Argives and Spartans to fall in a single day.

[Translation: A.M. Harmon, London/Cambridge Mass. 1915, slightly

adapted.]

More

than a century after the

Thyreátis had passed into Spartan hands, in 431 BC, the inhabitants of

the

island of Aegina were driven from their homes by the Athenians; the

Spartans

allowed them to settle in Thyréa (Thucydides 2.27 and 4.56; Pausanias

2.29.5). During the Peloponnesian War between Athens and

Sparta

(431-404 BC), the

Athenians and their allies raided the Kynourian coast with some

regularity; the

Athenian historian Thucydides, who chronicled this war, mentions such

attacks

consistently. In 430 BC, an expedition of 4300 men on 100 ships under

the

command of the Athenian political and military leader Pericles attacked

Prasiaí; the city was taken and destroyed (Thucydides 2.56.5-6).

Pericles - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Photo: Adam Carr,

Wikimedia Commons

Pericles - Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Photo: Adam Carr,

Wikimedia Commons

In

424 BC,

Thyréa suffered the same fate at the hands of the Athenian general

Nicias

(Thucydides 4.56-57). In 414 BC it was Prasiaí's turn again: the city's

territory was ravaged (Thucydides 6.105.2 and 7.18.3), after the

Argives had

already plundered the Thyreátis earlier that year (Thucydides 6.95.1).

In

the 4th century, Argos

regained the Thyreátis, after the defeat of the Spartan army by the

Thebans at

Leuctra in 371 BC and the subsequent Theban invasion of the

Peloponnese, which marked the end of Spartan hegemony over the

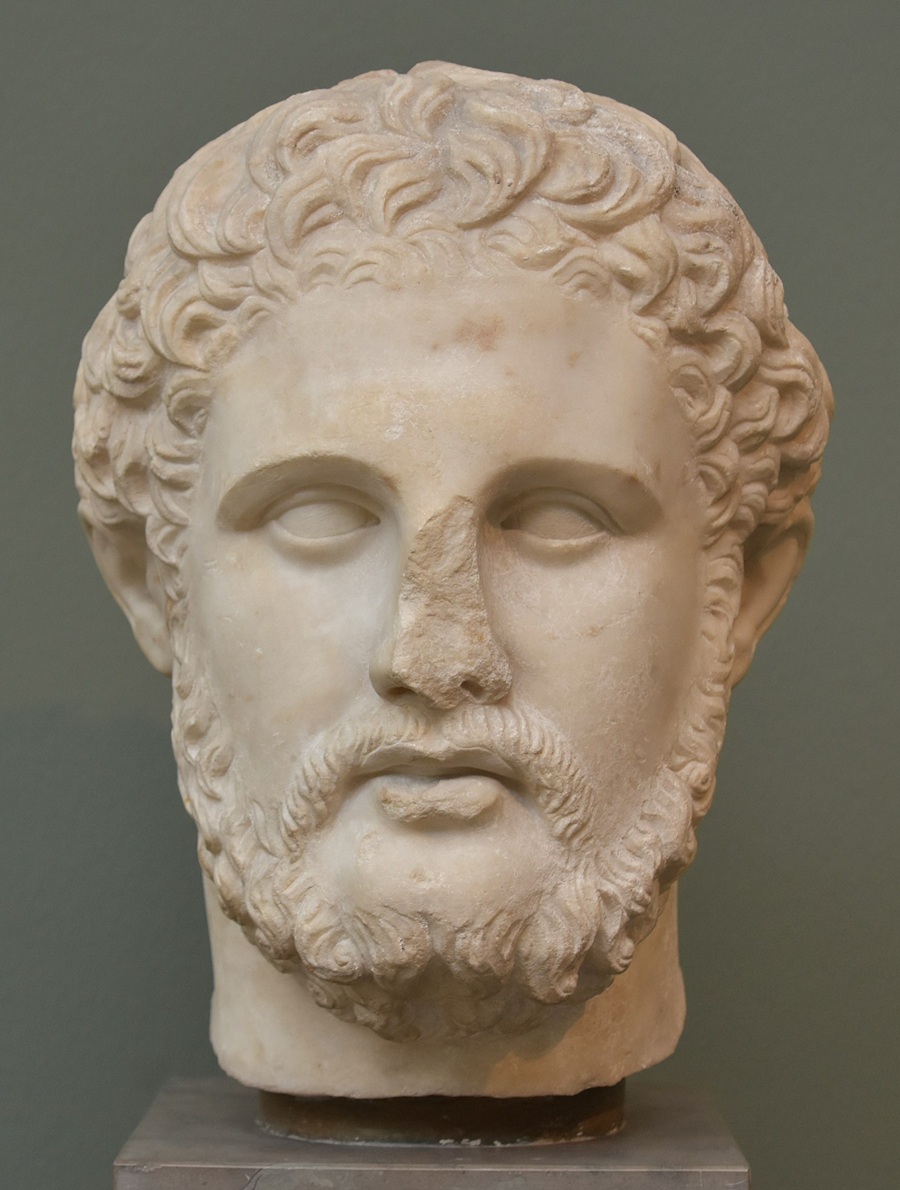

peninsula. Thanks to the intervention of the Macedonian king Philip II

(Pausanias 2.20.1, 2.38.5 and 7.11.2; Polybius 9.28.6-7 and 9.33.8-12),

Argos'

possession of northern Kynouria was confirmed in 338 BC.

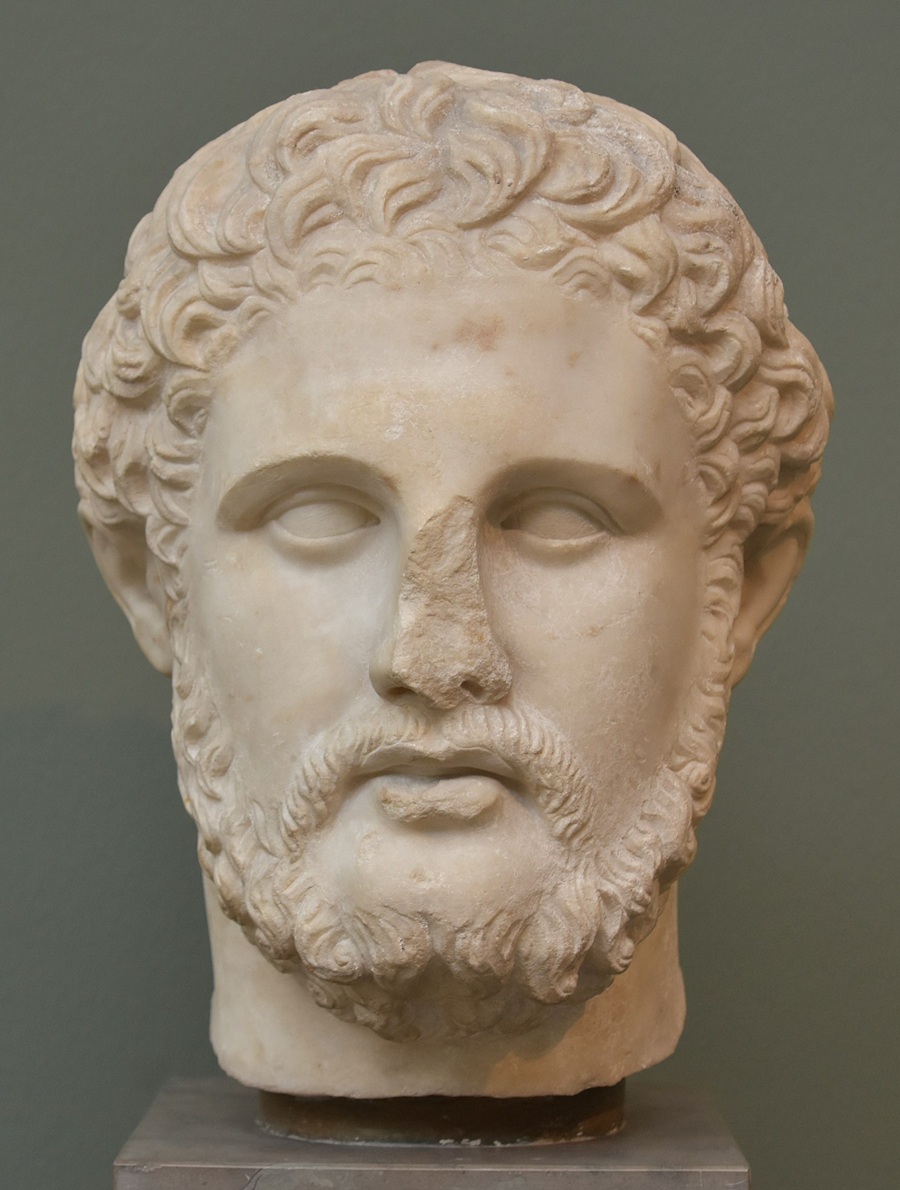

Philip II of Macedonia - Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek,

Copenhagen - Photo: Richard Mortel, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

Philip II of Macedonia - Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek,

Copenhagen - Photo: Richard Mortel, Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

In the 3rd

century

the Spartans also lost southern Kynouría. Around 275 BC, according to

an

inscription found at Delphi (Fouilles de Delphes III

I 68 = SIG (3) 407), Týros still

belonged to the 'Lacedaemonians'. But by 223 BC at the latest,

Zarax - south of Kynouría on the east coast of the Peloponnese - had

become

part of the territory of Argos (SEG 17.143), as must

have been the case

for more northerly coastal settlements such as Políchne, Prasiaí and

Týros. The Argive

conquest of southern Kynouría was probably part of the war between

Sparta on

the one hand and Macedonia and the Achaean League on the other during

the 220s;

Argos was a member state of the Achaean League.

Our

next data relate to the

so-called Social War (220-217 BC): a conflict between Macedonia, the

Achaean

League and Messene on the one hand, and the Aetolian League on the

other. In 219 BC, the

Spartans sided with the Aetolians; the Spartan king Lycurgus, according

to the

historian Polybius (Polybius 4.36), attacked southern Kynouría: he

retook

Prasiaí and Políchne, among other places, but besieged the fortified

inland village of Glympeís in vain. A year

later, near the same village, he forced a contingent of Messenians

allied to the

Achaeans into a humiliating retreat (Polybius 5.20).

Under Roman rule, Kynouría was

eventually divided: Argos remained in the possession of the Thyreátis,

Prasiaí became

part of the League of the Free Laconians, in which communities formerly

under

Sparta were organised. This is the situation found by

Pausanias (second-century

AD), author of a Description

of Greece (Pausanias 3.21.7 and 3.24.3). In the

same century, Herodes Atticus, Athenian plutocrat and Roman consul,

owned a magnificent

villa in the Thyreátis.

Herodes Atticus - Louvre, Paris - Photo: Alphanidon,

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Herodes Atticus - Louvre, Paris - Photo: Alphanidon,

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Such villas usually combined an economic and a

recreational function: they were pleasant places to live, but the

northern

plain of Kynouría also offered good opportunities for growing a variety

of

crops. Herodes Atticus was fabulously wealthy and spent his ample

financial

resources on several major building projects, including the famous

odeon (auditorium)

at the foot of the Athenian acropolis.

I have not found that much about the history of

Kynouría after Antiquity, nor have I looked very hard. In the period

between

600 and 800, Slavic tribes settled in the Peloponnese, and this may

not have left Kynouría completely untouched. In northern Kynouría and

the

neighbouring parts of Lakonía and Arkadía, place names that sounded too

Slavic

for the tastes of the authorities were still in use at the beginning of

the

twentieth century. Some of them were replaced by Greek toponyms. For

example,

the present village of Élatos was called Dragalevós

until 1926, Elaiochóri

Másklina until 1927, and Karyés Aráchova

until 1930. Other Slavic names have

survived, e.g. Meligoú.

In

the 13th century, Kynouría was

for a time part of

the Principality of Achaea, which had been carved out of the Byzantine

Empire by participants ('Franks') in the Fourth Crusade (1204). The

castle on

a

hill

south of Áyios Ioánnis in northern Kynouría (Κάστρο της Ωριάς,

'Castle

of the Fair Maiden') was

probably built around

the mid-13th century by the Frankish prince of Achaea, Guillaume de

Villehardouin. Meanwhile, Venice started to establish strongholds along

the coasts. The Frankish domination of Kynouría did not last long.

In 1262, the main fortresses of the south-eastern Peloponnese, such as

Monemvasía and Mystrás, were returned to the Byzantine emperor in

exchange for the Frankish knights captured in the Battle of Pelagonia

in 1259 (one of those freed was Guillaume de Villehardouin himself).

Information is scarse and ambiguous, but it seems that from 1272

Kynouría was firmly in Byzantine hands. For the next century

and a half, the south-east

was used as a base for the recapture of the peninsula from the

Franks. This resulted in the establishment of the Despotate of Mystrás

around the middle of the 14th century. It was a province of the

Byzantine empire, governed by a member of the imperial dynasty. The

Venetians may have taken over the area around Ástros in the early

15th century. By 1430, the Frankish power in the Peloponnese had been

eliminated, but in 1460 the peninsula was conquered by sultan

Mehmet II, who had taken Constantinople seven years earlier. For the

time being, a number of Venetian fortresses remained outside Ottoman

control, and the same may have been true of (part of) Kynouría.

Incidentally,

when reading about the history of the Peloponnese after Antiquity, it

is helpful to know that during the Middle Ages and early modern times,

the peninsula was usually called the Morea (Byzantine Greek: Μορέας,

Modern Greek: Μοριάς). For example, the 'Despotate

of Mystrás' was also called the 'Despotate of the Morea' (Δεσποτάτο του

Μορέως).

Kynouría

probably fell into Ottoman hands around

1540, at the same time as the two main Venetian fortresses in the

eastern

Peloponnese, Náfplio in the north and Monemvasía in the south. In the

1680s, the Venetians returned and conquered the Peloponnese, but in

1715 they were driven out again by the Turks. Like other regions of the

Peloponnese, Kynouría thus experienced two periods of Ottoman rule, the

first Tourkokratía

(before c. 1685) and the second (after 1715). The

south-eastern Peloponnese was an economically prosperous region under

Ottoman rule. Not only did the water-rich region around the

Párnonas produce a wide range of agricultural products, but the

inhabitants of towns such as Prastós also earned well from overseas

trade. Merchants from Kynouría often settled for a time in

Constantinople,

importing butter from Russia and the Crimea and selling it elsewhere in

the Ottoman Empire. In the 18th century, they began to participate in

maritime trade networks across the Mediterranean. The money earned was

spent in the country of origin, including on the construction and

decoration of mansions, churches and monasteries. The

coastal town

of Leonídio became a new regional centre. On these developments see

Arisoy 2018; Balta 2009.

During the Greek war of independence, the region

was devastated by Ibrahim Pasha who, at the behest of the Sultan, began

to reconquer

the Peloponnese in 1825. He was finally stopped at Navarino, where his

fleet

was destroyed by the English, Russians and French (1827). It was during

these

years that Prastós, traditionally the most important town in Kynouría,

and Moní

Loukoús, a monastery near Ástros, went up in flames. Earlier, in 1823,

the

second national assembly of the Greeks had met in Ástros to adopt a new

constitution and form a national government.

Some information about

Kynouría in the second world war can be found in two articles by

Stratís Kouniás, on the

website

www.leonidio.gr, and on the website of the mountain village of

Kosmás. A

garrison of Italian carabinieri was stationed in Leonídio until the

summer of

1943. In August of that year, these were driven out by the partisans of

the

communist-led resistance movement EAM, who had defeated the Italians at

Kosmás

in late July. In that battle, the Italian governor of Trípoli had been

killed.

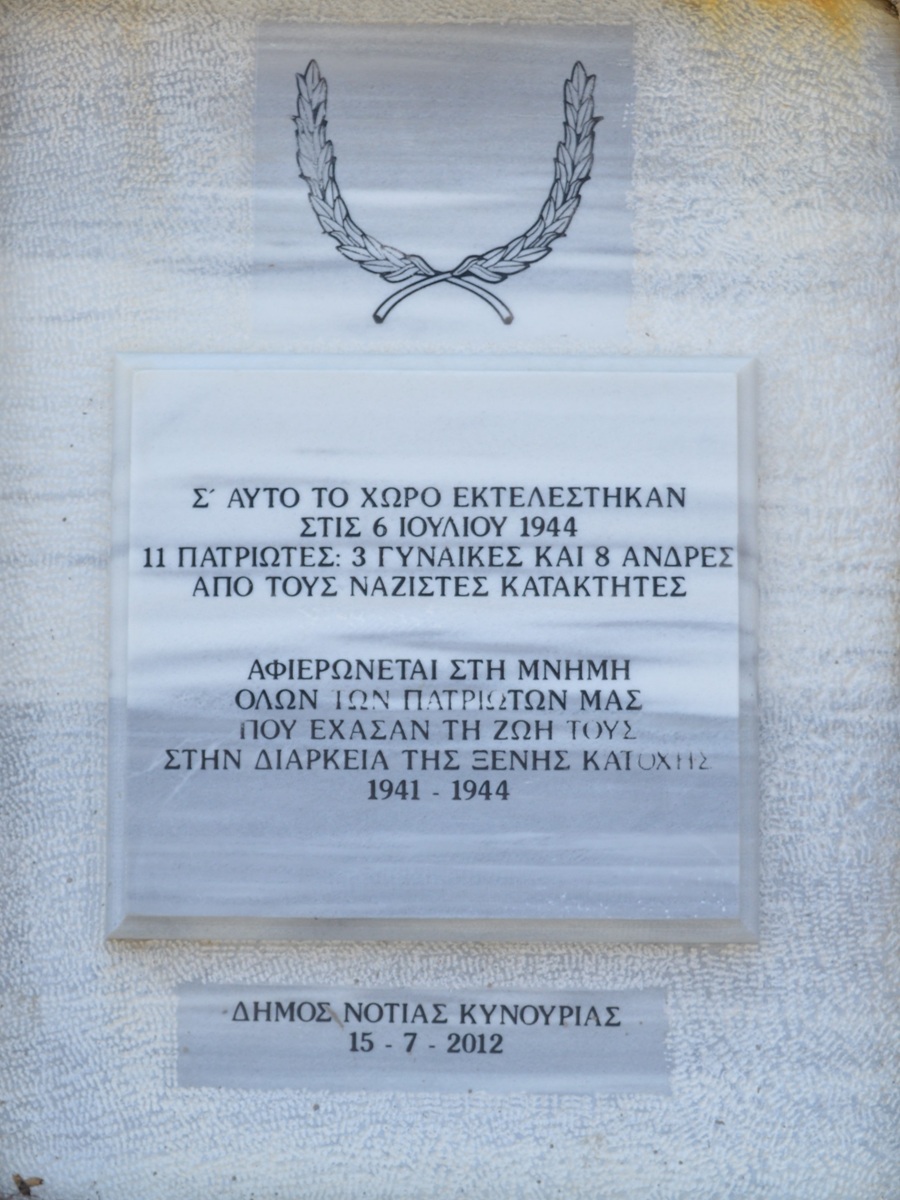

Monument for the

Battle of Kosmas (1943) - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2013

Monument for the

Battle of Kosmas (1943) - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2013

By the summer of 1943, most of Kynouría was controlled by EAM

partisans, but in 1944 the Germans, aided by Greek

collaborators, carried out repeated attacks in the region. In January

1944,

Kosmás went up in flames. In late June/early July (i.e. during or

immediately

after the grain harvest) of the same year, the last and largest German

attack

took place. On that occasion, according to Stratís Kouniás, 400-500

civilians

were killed. The Germans executed non-combatants and captured partisans

and

transported about 600 people to Germany as forced labour. Some

prisoners were

used as hostages to deter attacks on trains: they were locked in cages

linked

in front of locomotives. Eleven prisoners were shot at Leonídio on 6

July.

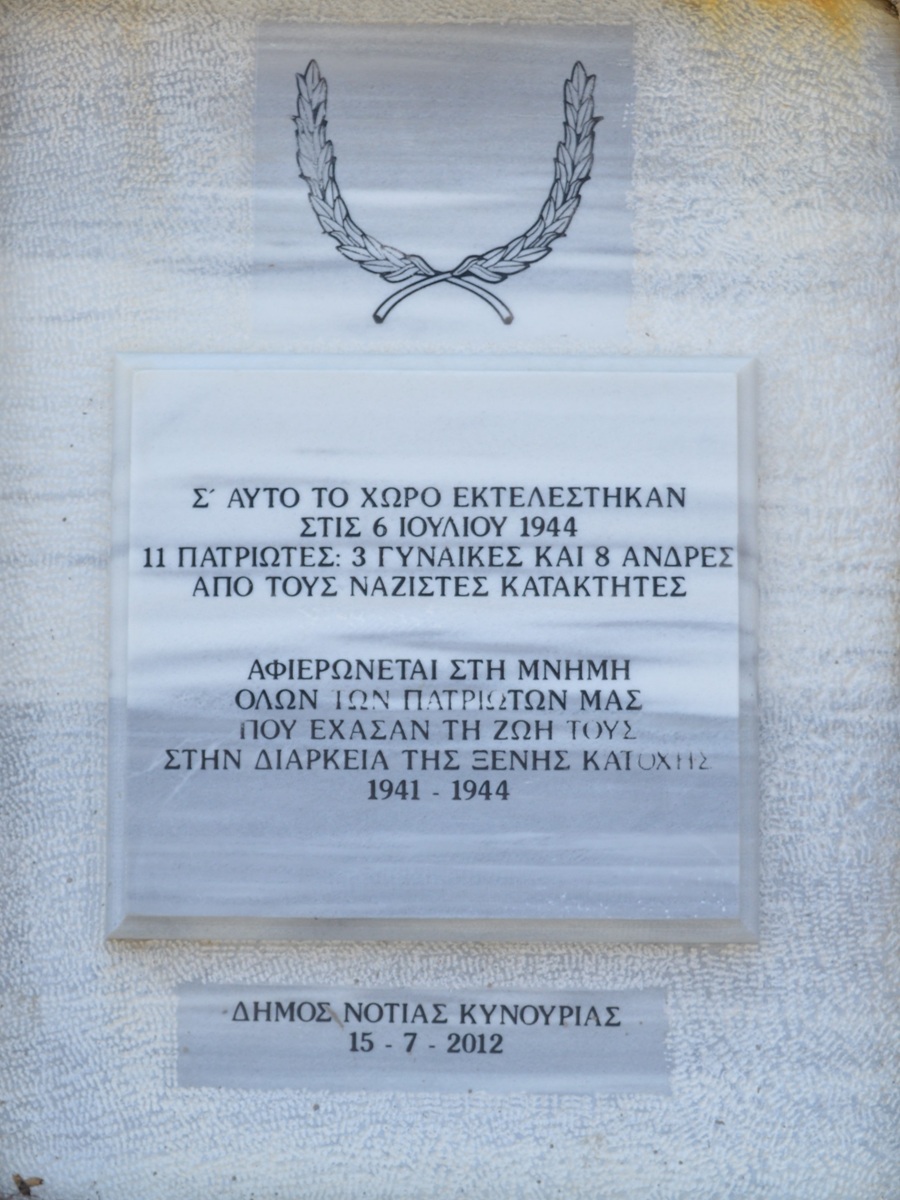

Two memorials recalling these events.

On the left, a monument to 48 non-combatants from Áyios Pétros who were

killed

by the occupying forces in the last June days of 1944. On the right, a

memorial plaque

to the eleven executed in Leonídio.

Photos: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015 (left) and summer

2017 (right)

Photos: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015 (left) and summer

2017 (right)

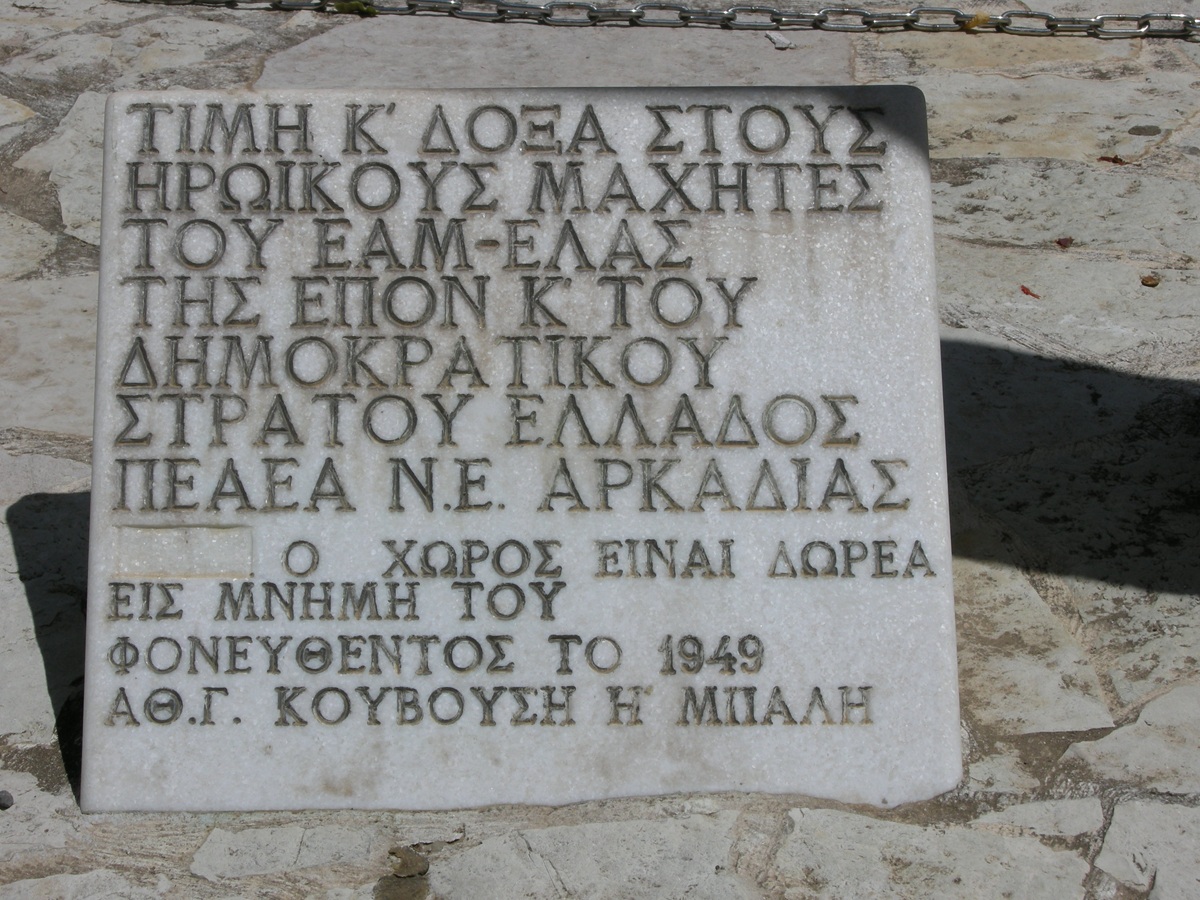

In

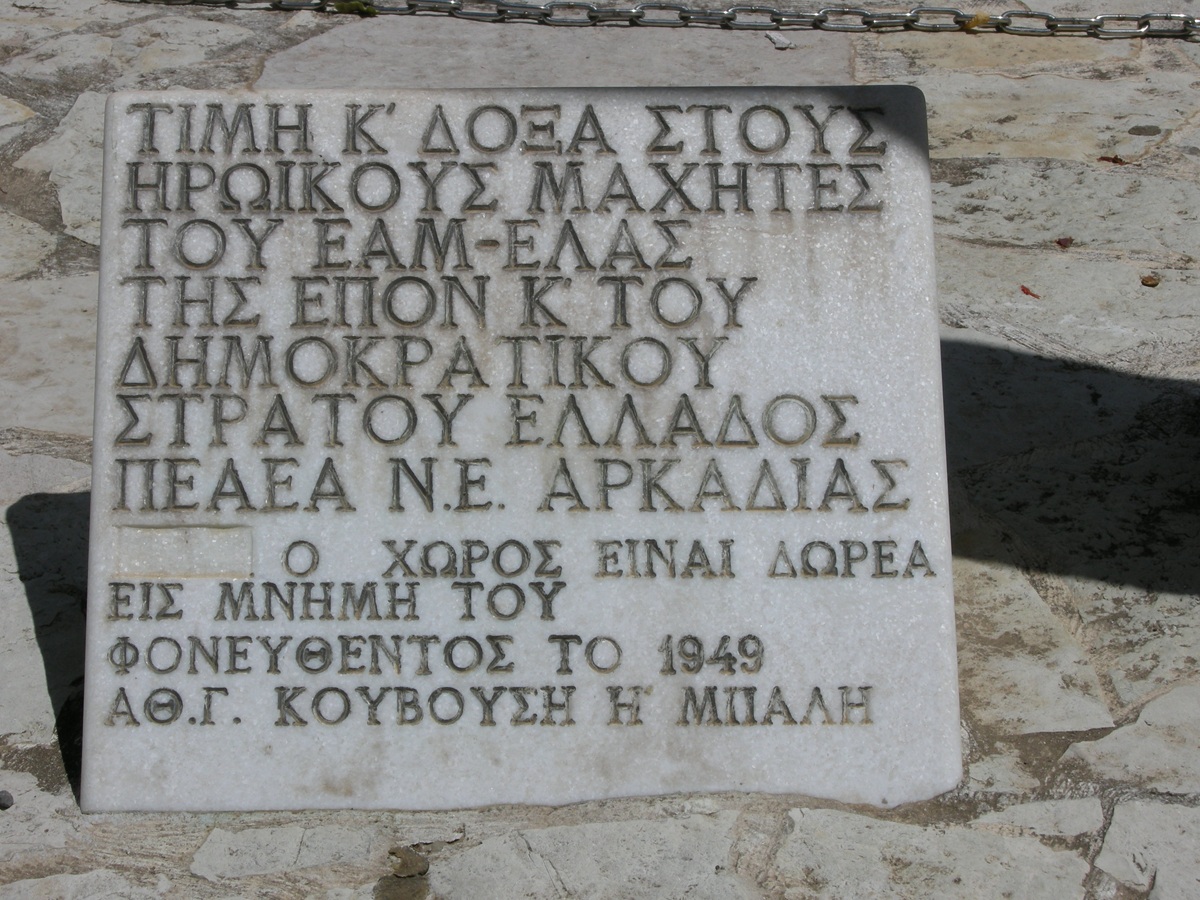

the Greek civil war, the last

major battle in the Peloponnese, in January 1949, took place at Áyios

Vasíleios, in the southern Párnonas Mountains; more information on the

Greek civil war in Kynouría can be found here.

Sights

around Ástros

About four kilometres

north-west of Ástros

(satellite photo), to the right of

the road to Tripoli, lie the remains of a

villa

belonging to the Athenian billionaire Herodes Atticus

(101/3-177/9 AD),

one of the richest and most influential men of the Roman Empire in the

second

century AD and a prominent representative of the so-called Second Sophistic.

Already in the first half of the 19th century, the site was visited by

travellers such as William Martin Leake from England, Guillaume-Abel

Blouet from France, and Ernst Curtius from Germany; at the

beginning of the 20th century, the Greek archaeologist Konstandinos

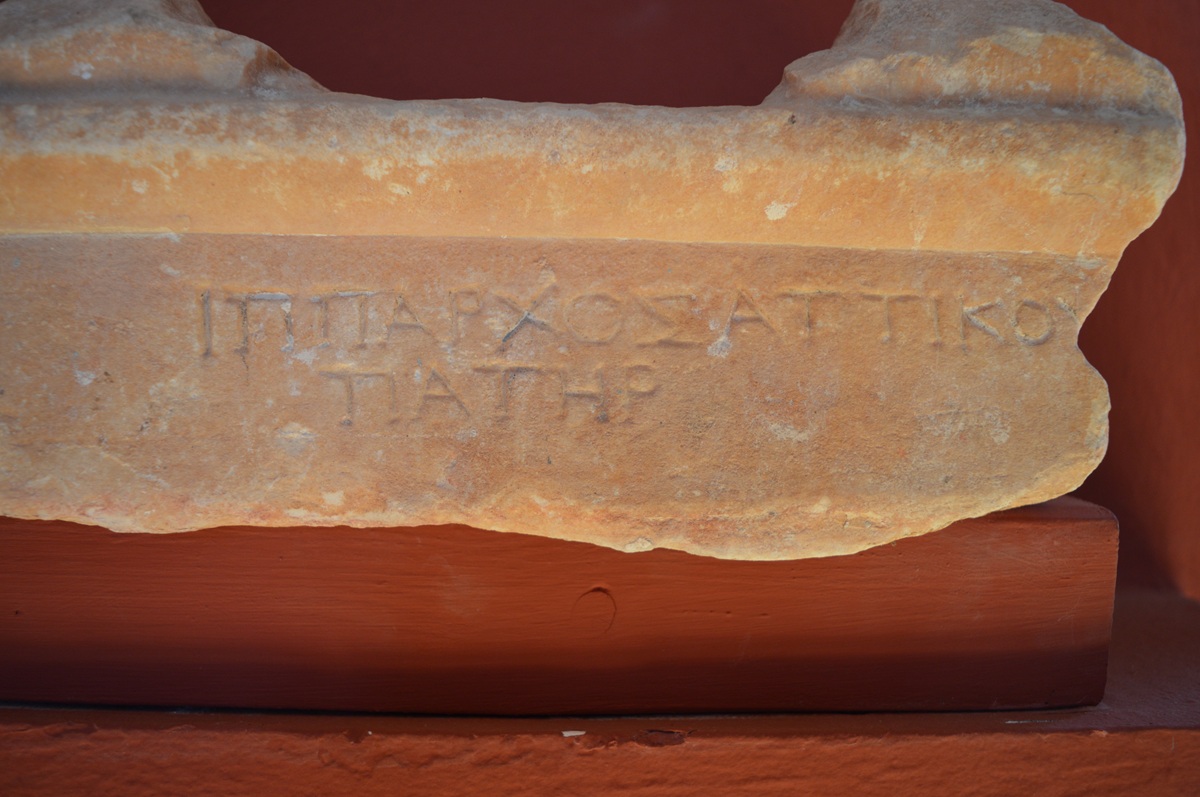

Romaios

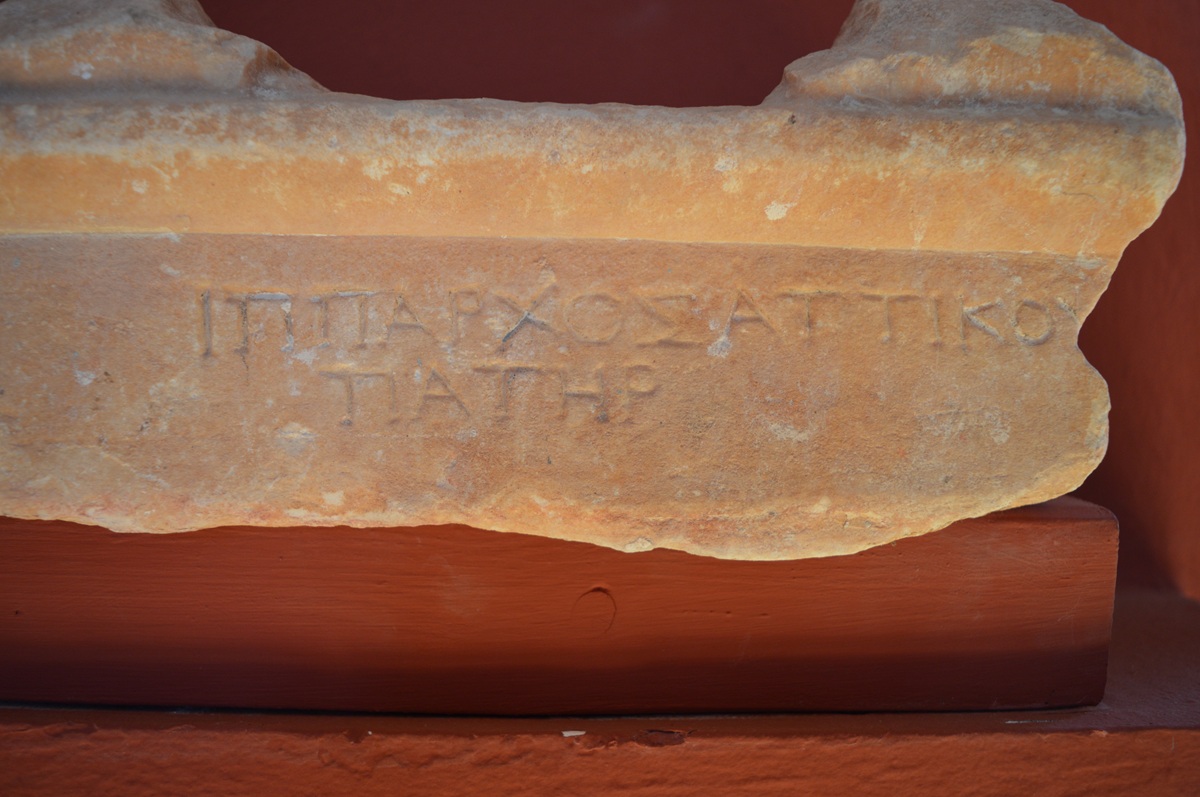

identified it as the site of a villa of Herodes. The identification was

based

in part on the inscription below, which mentions the names of Herodes'

grandfather (Hipparchos) and father (Attikos): ΙΠΠΑΡΧΟΣ ΑΤΤΙΚΟΥ |

ΠΑΤΗΡ,

'Hipparchos, father of Attikos'.

Inscription from the

villa of Herodes Atticus: 'Hipparchus, father of Atticus' - Photo:

Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

Inscription from the

villa of Herodes Atticus: 'Hipparchus, father of Atticus' - Photo:

Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

A striking confirmation of Romaios'

identification of the site came in 1995, with the discovery of a

similar

inscription reading ΑΛΚΙΑ ΗΡ[ΩΔΟΥ] | ΜΗΤΗ[Ρ], 'Alkia, mother of

Herodes' (photo

below). Cf. Spyropoulos 2006,

pp. 29-30. Presumably, in both cases we are

dealing with the architrave of a shrine in which an effigy of an

(ancestral)

parent was placed.

Inscription from the

villa of Herodes Atticus: 'Alcia, mother of Herodes' - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

Inscription from the

villa of Herodes Atticus: 'Alcia, mother of Herodes' - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

During

the years 1980-2001, the villa was systematically

excavated by Greek

archaeologists. The central, also largest part of

the

complex was formed by an elongated enclosed garden with a west-east

orientation

(actually it is northwest-southeast, but we are not going to make it

too

difficult and call the long sides the north or south side and the short

sides

the west or east side). The garden was surrounded on three sides by a

colonnade; the floors of the colonnade were decorated with mosaics.

Including

the colonnade, this part of the complex measured about 80 by about 32

metres.

An artificial watercourse around the garden was fed from a spring

building

('nymphaeum') on the fourth, western side. On the eastern side of the

garden,

behind the colonnade, were a dining hall, living quarters, and a

so-called 'Gartenstadium', which opened to the east with, again, a

colonnade. From here, Herodes and his guests had a magnificent

view over the

northern part of the plain of the Thyreátis (or, to use its modern

name, the plain of Ástros) and the Argolic Gulf.

View from Herodes'

villa - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

View from Herodes'

villa - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

To

the north of the enclosed garden was a

structure referred to by the excavators as 'Repräsentationsbasilika';

it dates

from the second half of the first century AD and is the oldest part of

the

villa. To the west of the garden was a second basilica. On the south

side of

the complex were several buildings, the easternmost of which (also a

basilica)

was, according to the excavators, a sanctuary for Antinous, the youth

loved by the Emperor Hadrian. Antinous had drowned in the Nile during

an imperial

visit to Egypt in the fall of 130 and had been deified on the

inconsolable

emperor's orders. The site is not open to the public, but a walk along

the fence gives a

reasonable impression of the complex, as shown in the photo below,

taken in

2008. The walls in the foreground are what remains of the sanctuary for

Antinous.

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, sanctuary of Antinous - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, sanctuary of Antinous - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

During a visit in 2011, the site was

still closed to the public, but it appeared that a roofing project was

in progress to make the villa accessible as an open air museum. The

photo below was taken from the

northern fence. In the foreground are the remains of the

'Repräsentationbasilika'.

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, 'Repräsantationsbasilika' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer

2011

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, 'Repräsantationsbasilika' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer

2011

Much more informative photos than

these were taken by people who had permission to walk around beyond the

fence

or who visited the excavation when it was not yet fenced off. Such

photos can

be found, for example, in the Classical archaeological image collection

of

Aarhus University in Denmark (search for 'Loukou') or on Dr

Heinz Schmitz's

website (scroll to 'Eva Dolianon Loukous'). The photo below,

taken from this

website, shows the enclosed garden, seen from the east. More photos here: a pdf

file of photos that is part of Parálio Ástros' site,

www.astrosparalio.gr

(three photos taken from a high position that give a good view of the

site's

floor plan, and two photos of mosaics). Green with envy I became when

looking

at this travel blog from 18 May 2011:

'There was a tall fence all around the

site but the main gate was open with an unlocked padlock hanging on it.

There

was nobody on the site so we went in and spent some time looking

around.' Nice

photos of the Repräsentationsbasilika and the central garden. What is

worrying,

of course, is that (i) the site was apparently completely unguarded;

and (ii)

the writers of the travel blog could not observe any activity on the

site ('It

was quite obvious that no work had been done on the site for some time

so it is

anyone's guess when it will be finished.'). During my last visit to the

site

(summer 2019), nothing could be seen of the roof under construction

from summer

2011. It is to be feared that the opening as an open air museum of

Herodes'

villa has become one of the victims of the dire state of Greek state

finances.

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, the enclosed garden from the east - Photo: Dr. Heinz Schmitz

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, the enclosed garden from the east - Photo: Dr. Heinz Schmitz

Jennifer Tobin, in her study of

Herodes Atticus, tells us that there was a lime kiln on the

site; over time –

the kiln was not deactivated until 1960 – a lot of sculpture must have

disappeared into it. (Meanwhile, lime kilns as reminders of a bygone

era have

also become objects of nostalgia: see the fine photos here.) But a fair amount

of sculpture has survived, such as a cult statue of Antinous, depicted

as the

god Dionysus (here, scroll down to 'Astros');

portraits of the emperor Hadrian,

of Lucius Aelius Caesar, Hadrian's intended successor (died in 138 AD),

of Herodes' foster sons Polydeucion and Memnon and of Herodes himself;

an Attic

votive relief for Asclepius from the 4th century BC; and a replica of a

sculptural group of Achilles with the amazon Penthesileia. This replica

was displayed

in the southern colonnade of the enclosed garden; according to the

excavators,

this sculptural group corresponded to a replica of the so-called Pasquino group

on the north side (but remains of it were last seen on the site by the

British

traveller Leake, in the early 19th century: Travels in the Morea,

volume 2, p. 488f.). Six amazons (photo below; see also Blouet's drawing) served as caryatids,

supporting the eastern

colonnade according to the excavators. Their arrangement corresponded

to that on the west side, in six

niches in the wall of the nymphaeum, of freestanding statues, one of

which has

been completely recovered. According to one of the excavators, G.

Spyropoulos,

these were the Saltantes Lacaenae of Callimachus, a

famous sculptor of

the late 5th century BC. Herodes is supposed to have acquired these

Classical

statues of dancing Spartan women, mentioned by Pliny (Naturalis

Historia

34.92), and placed them in his villa. Photographs taken from

publications by

Spyropoulos (including the statue of the dancing woman and the

Achilles/Penthesileia group) can be found here.

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, Amazon-Caryatid - Athens, National Museum (NM 705) - Photo:

www.livius.org

Villa of Herodes

Atticus, Amazon-Caryatid - Athens, National Museum (NM 705) - Photo:

www.livius.org

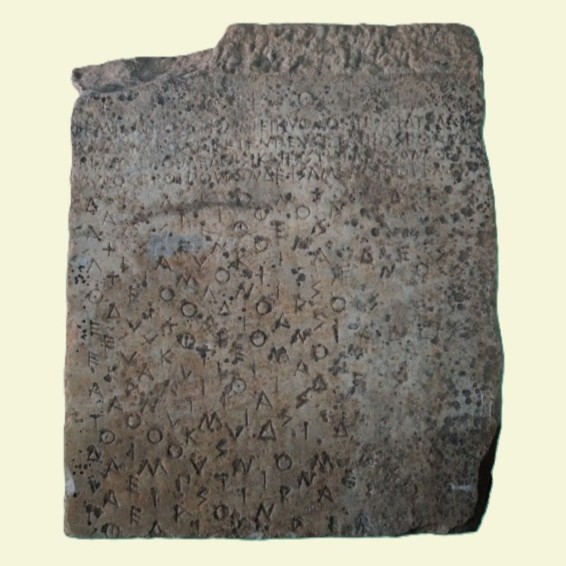

Apparently,

Herodes had little qualms about removing Classical remains from what

may have been their original context and

transferring them to his villa. The most startling example of this

willingness

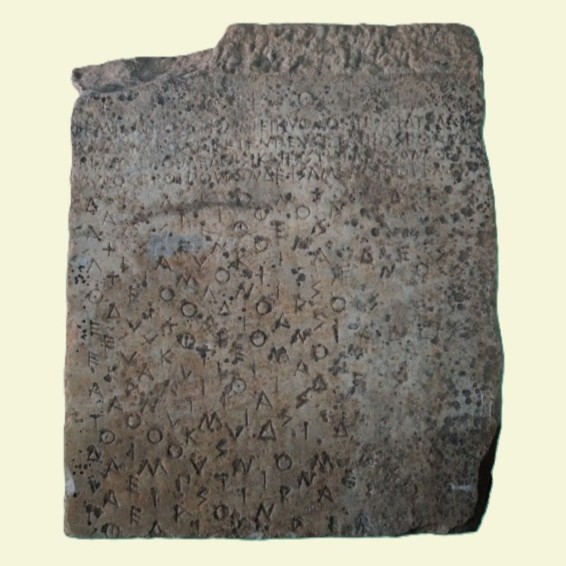

is an inscription listing war dead

from the Athenian phyle

Erechtheis. According to the four-line epigram above the list,

those mentioned had died in battle

against the Persians. It does not seem impossible that this is what

remains of

the ten tombstones – one for each of the ten phylai ('tribes')

into

which the

Athenian citizenry had been divided since the late 6th century BC –

that once

marked the final resting place of the Athenians killed at the battle of

Marathon.

Stele of the dead of

the Erechtheis tribe - Archaeological Museum

of Astros inv.no. 535 - Hellenic Ministry of

Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

Stele of the dead of

the Erechtheis tribe - Archaeological Museum

of Astros inv.no. 535 - Hellenic Ministry of

Culture and Sports/Archaeological Receipts Fund (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

This tomb was described by

Pausanias about 160 AD (Description

of Greece 1.32.3). Herodes Atticus himself was from the

Athenian deme of Marathon

and was born into a family that claimed to be descended from Miltiades,

the

Athenian commander in the famous confrontation with a Persian landing

army in

490 BC. In addition to the inscription listing the fallen of the phyle

Erechtheis, fragments of two other similar inscriptions (same shape of

the

letters and layout) have also been found on the site of the villa. On

the basis

of these finds, G. Spyropoulos has formulated the rather adventurous

hypothesis

that Herodes had the entire funerary monument transferred from Marathon

to his

villa in Kynouría, thus enriching his Peloponnesian villa with a

tangible

reminder of the glorious past of his native city and his lineage. At

Marathon,

he would have raised the burial mound that can still be admired there,

which

would therefore have been there not since the 5th century BC, but since

the 2nd

century AD. Some scepticism about this reconstruction is in order. In

order to

make it plausible that the burial mound dates not from the 5th century

BC, but

from the 2nd century AD, one would at least have to be able to prove

the presence

of material in the mound from the period between the 4th century BC and

the 1st

century AD. In a

Greek-language publication, The Tombstones of the

Fallen in

the Battle of Marathon from Herodes Atticus' villa at Éva in Kynouría

(Athens 2009), Spyropoulos refers on this point to a more detailed

analysis in

a forthcoming book. Walter Ameling, in a

2011 article, rejected this part of

the hypothesis: he saw no reason to believe that the monument at

Marathon completely

changed its appearance around the middle of the 2nd century AD.

As for the authenticity of the inscription,

Ameling was reluctant to commit himself, but pointed out that the shape

of the

letters and the layout made it less plausible that this was an Imperial

imitation. The peculiar layout is further discussed in a 2012 article

by

Catherine Keesling: one line is reserved for each name on the

inscription, and the

letters of each line are deliberately placed between the letters

directly above

them. Keesling points to parallels for this layout in Attic

inscriptions from

the late 6th and early 5th centuries BC. The idea that one of the ten

tombstones for the Athenians killed in the battle of Marathon was

actually

found in the villa at Ástros is currently fairly widely accepted

(although there

are sceptical voices, see for example here).

The first serious scholarly

publication of the text of the inscription was by G. Steinhauer, Horos

17-21 (2004-2009), 679-692. As published by Steinhauer, the inscription

has

since been included in the Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum

(SEG

LVI 430); the SEG is the annual compilation of all

newly discovered

Greek inscriptions (and of new publications on previously published

epigraphic

texts). Steinhauer also briefly discusses the find in Herodes' villa in

a book

on Marathon. He does not seem to have any doubts about the

authenticity of the

inscription, but he does not take Spyropoulos' theory about the burial

mound at

Marathon at face value. Some suggestions for improving the text as

published by

Steinhauer and a revised English translation can be found in a post by

Pierre

MacKay on this blog on 9 April 2011; there

is also a rather sharp

black-and-white photograph and a drawing of the stone. A German

translation can

be found here.

An important contribution to

the reconstruction of the text of

the inscription (especially the first line of the epigram is

problematic) can

be found in a 2014 article

by Richard Janko. He also presents a 'normalised

transcription and translation into English elegiacs' of the epigram.

For full discussion and more recent bibliography see Strazdins 2023,

174-192.

The sovereign appropriation of

Athenian heritage by Herodes Atticus takes on an added significance in

the

light of his own burial and the vicissitudes of his tomb. A fascinating

article

on the subject was published in 2008 by Joseph L. Rife, from whom I

borrow the

following details. Herodes himself had expressed a desire to be buried

in

Marathon. After all, that was where he came from. But when the sophist

exchanged the temporary for the eternal in the late 170s, the Athenians

did not

respect his last wish: they wanted to give the great deceased an

official

burial in the city. No sooner said than done: the corpse was seized,

carried in

procession to the city by the Athenian ephebes, and buried near the

marble

stadium that Herodes himself had built for the Panathenaean games of AD

140;

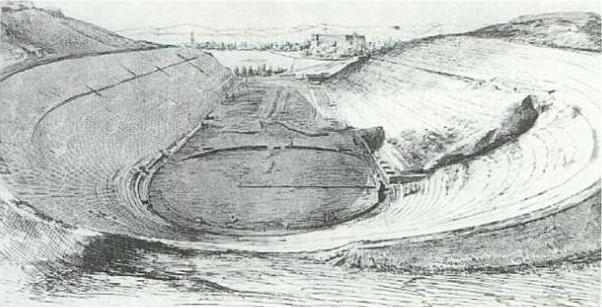

according to Rife, the remains of the tomb lie above the stadium, in

the

accompanying image on the right.

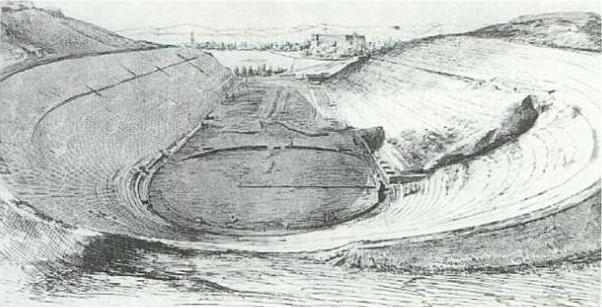

The Panathenaic stadium after the excavations of 1869/70

The Panathenaic stadium after the excavations of 1869/70

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

During

or shortly after the funeral, an altar

stone dedicated to 'Herodes, the heros of Marathon'

was placed at the

tomb; as such, the deceased was apparently the object of cultic

veneration.

Rife, who seems to have been unaware of the find at the villa near

Ástros when

he wrote the article, rightly points out that the designation 'heros

of

Marathon' must inevitably have evoked associations in the minds of

passers-by

with the Athenian hoplites who had fallen in battle against the

Persians in 490

BC. The inscription on the altar stone was intended to have much the

same

effect as a burial in Marathon itself: a lasting link between the

memory of

Herodes and the memory of the historic battle. Unintentionally,

however, the

inscription on the altar stone must also have recalled how, less than

20 years

earlier, Herodes had interfered with the monument to the fallen at

Marathon.

The sophist had always been a controversial figure in his native city,

and many

Athenians will not have mourned his death too much. Disagreements

between large

sections of the Athenian citizenry and Herodes had led to a trial

before the

emperor Marcus Aurelius as recently as 174. His appropriation and

relocation to

the Peloponnese of a national monument hors catégorie

will not have met

with universal approval. Probably within a few decades of the sophist's

death,

someone removed the name of Herodes from the altar stone to the heros

of

Marathon and also chiselled away the name of the stone's founder. We do

not

know what moved an unknown person to take up the chisel, but it is an

attractive conjecture that, among other things, he was offended by

Herodes'

treatment of the tombstones of the true heroes of Marathon.

Incidentally, Herodes'

sarcophagus was reused shortly after 250, some three-quarters of a

century

after his burial. '[H]is memory at Athens had (...) shifted

dramatically', Rife

concludes.

Enough of Athens, back to

Kynouría.

The Archaeological Museum of Astros,

which houses most of the finds from Herodes' villa, has

been closed for years. I myself benefited from a brief opening

in July 2019. Many of the larger finds from the more recent excavations

of the

villa during the 1980s and 1990s were still in storage, but

what was on display was well worth a visit. The museum also has

exhibits from other archaeological sites in Kynouría, such as the

sanctuary of Apollo Tyritás on Profítís Ilías between Tyrós and Mélana

(see

below).

And even without the antiquities

collection, visiting the museum is rewarding for its beautiful garden

and for the

fact that it is a lieu

de mémoire in its own right: in 1823, the second

national

assembly of the nascent Greek state met here.

The Archaeological

Museum of Ástros - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

The Archaeological

Museum of Ástros - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

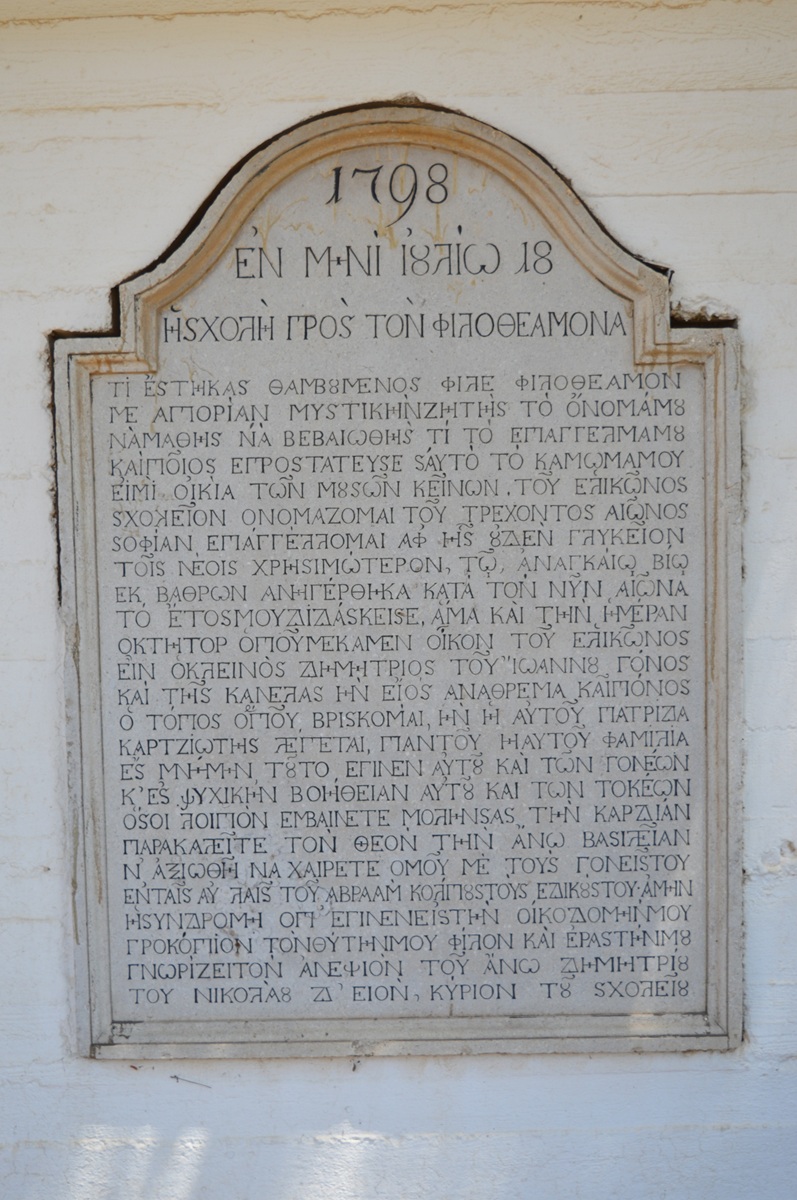

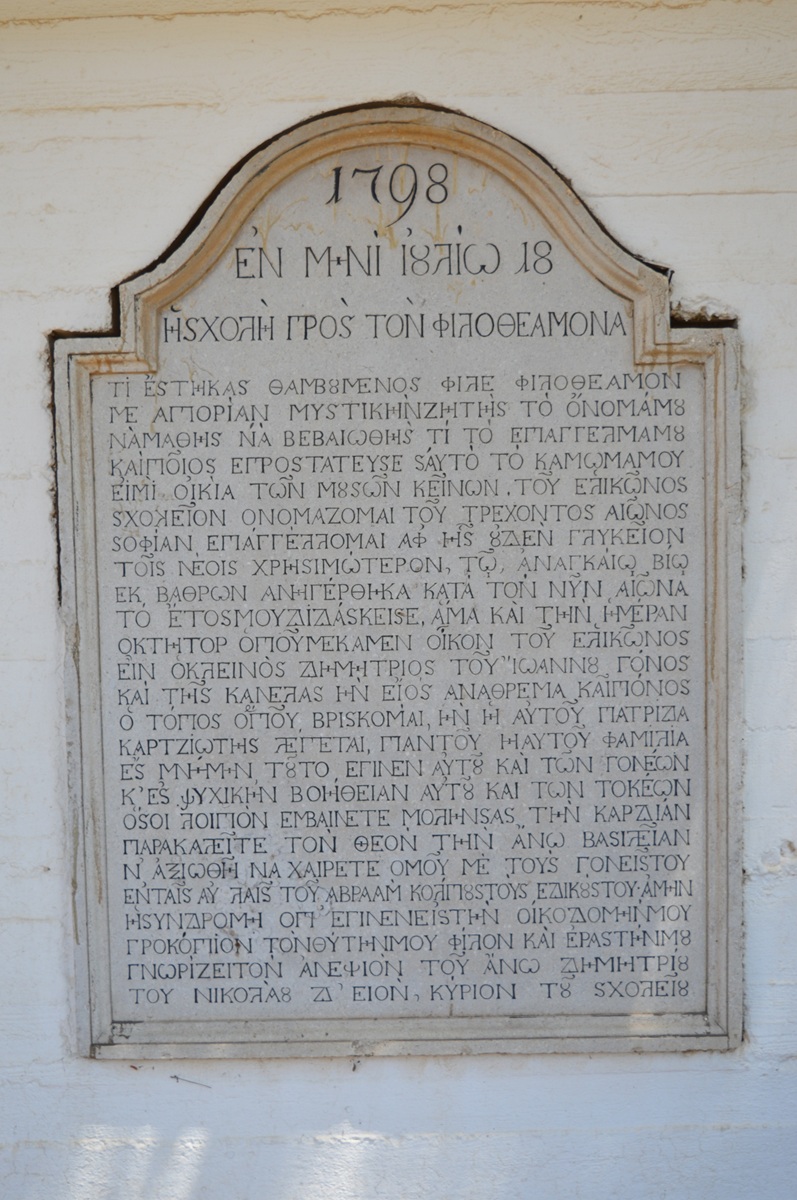

The museum is a former

secondary

school. It was founded in 1805 as an annex to the school established in

the

village of Áyios Ioánnis in 1798 by the local benefactor Dimítrios

Karytsiótis

(1741-1819),

who had amassed a fortune as a merchant in Trieste. Unlike the branch

in

Ástros, the school in Áyios Ioánnis did not survive the destruction of

the

village by Ibrahim Pasha, in 1826; only an inscription mentioning its

foundation remains (photo below). A transcription of the inscription

and some information about it can be found here

(in Greek). The school in Astros was also set on fire by Ibrahim's

army, but was restored and reopened in 1829. See on the schools of

Karytsiótis Arvaniti

2001-2002.

Áyios Ioánnis, inscription mentioning foundation of

Karytsiótis school - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015

Áyios Ioánnis, inscription mentioning foundation of

Karytsiótis school - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015

Some images

of sculpture

in the Museum of

Ástros, from the villa

of Herodes Atticus. Imperial portraits are well

represented, including those of Hadrian (117-138) (Spyropoulos 2006, p.

106

number

2, with image 16 on p. 105) and Marcus Aurelius (161-180) (Spyropoulos

2006,

pp. 107-108 number 3, with image 17 on p. 107). A striking feature of

Hadrian's

portrait is that instead of the usual Gorgon's head, the breastplate

bears an

image of the winged head of Antinous. The emperor's lover is identified

with

Perseus or Hermes by the wings in his hair, and this

heroization/deification

makes it plausible that this bust of the emperor was made in or after

the year

of Antinous' death (130 AD).

Portrait busts of the

emperors Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius from the villa of Herodes Atticus

- Photos:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

Portrait busts of the

emperors Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius from the villa of Herodes Atticus

- Photos:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Ástros)

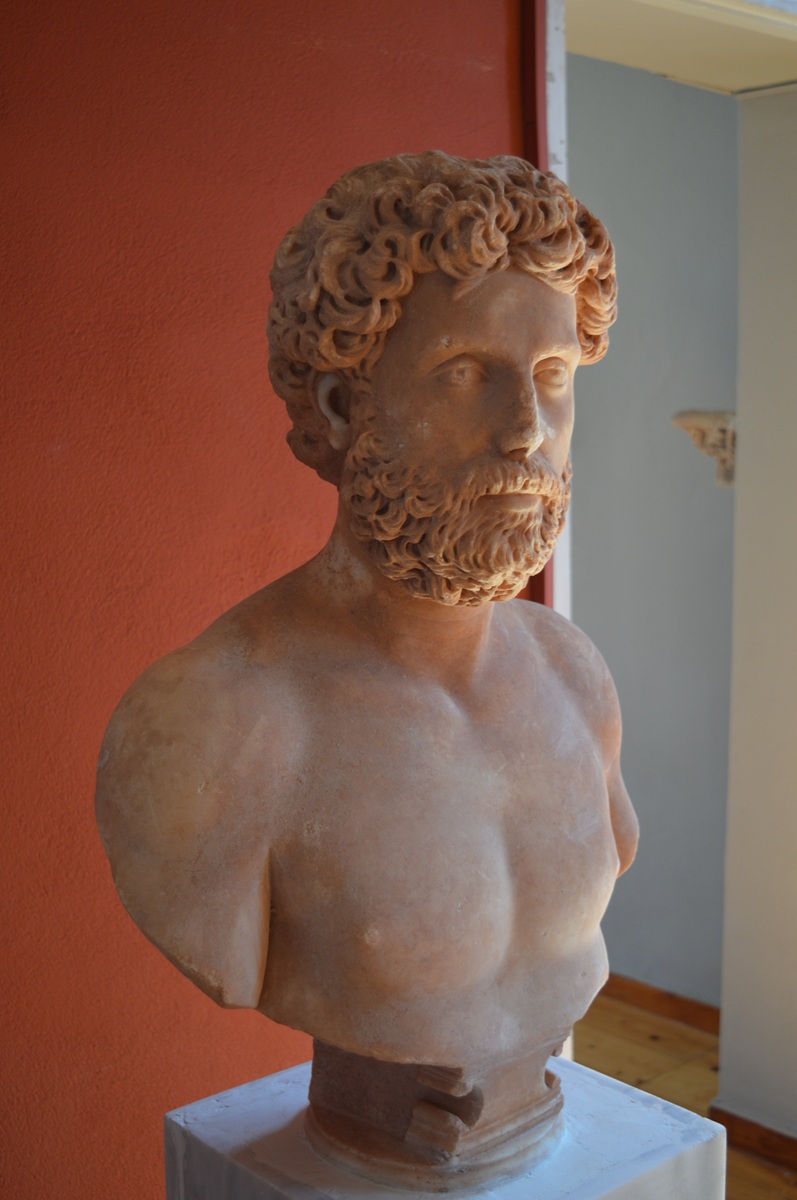

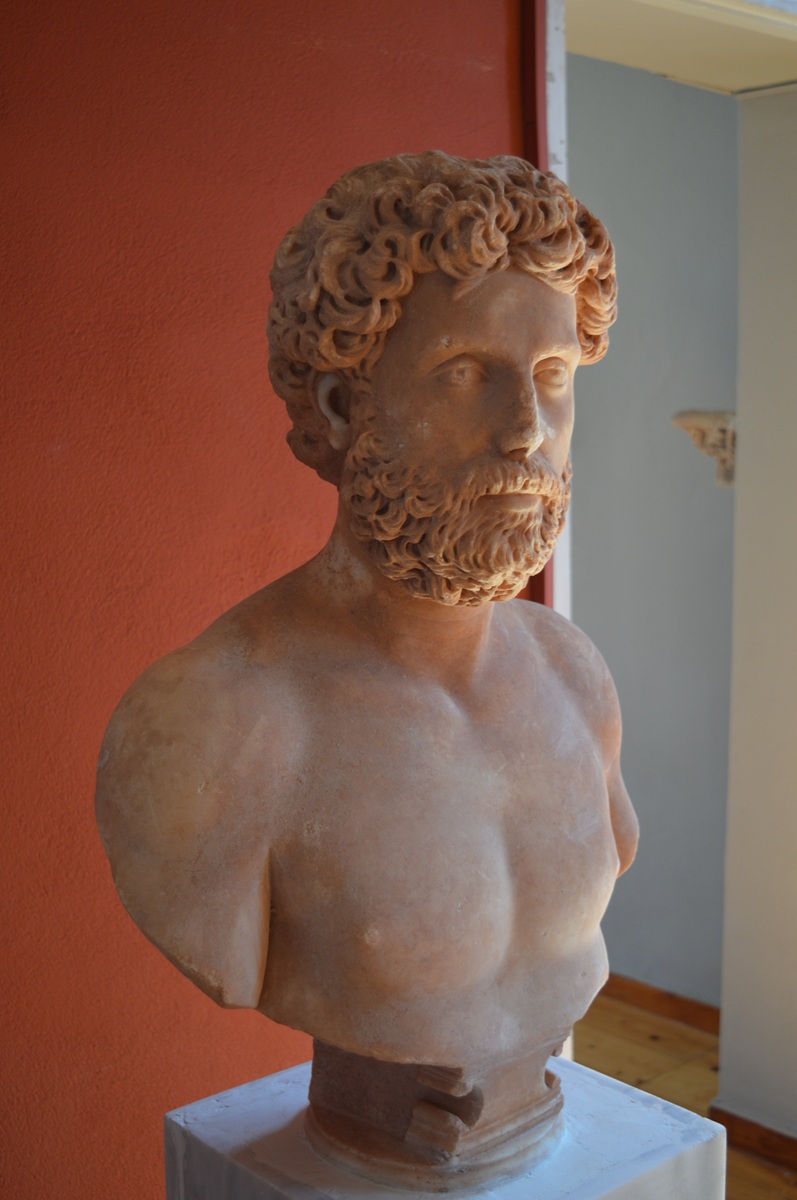

Personally, I find the following

portrait of an unknown man to be the highlight of the collection, a

magnificent

example of Antonine sculpture; the excavators of Herodes' villa date it

to the

reign of Marcus Aurelius (Spyropoulos

2006, p. 122 number 14, with image 28 on

p. 124).

Portrait bust of an

unknown man (second half 2nd century AD) - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer

2019 (Museum Ástros)

Portrait bust of an

unknown man (second half 2nd century AD) - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer

2019 (Museum Ástros)

Finds from Herodes' villa are also on

display at the Panarcadian Archaeological Museum in Trípoli and the

National

Archaeological Museum in Athens. In Athens, Jona Lendering took the

picture

below of a relief depicting a young man for me (the museum number is NM

1450;

the relief measures 97 by 68 cm). The vase on the column on the right

is a loutrophoros;

such vases were regularly used as grave markers. The relief was made

after the

death of the boy depicted, but he had become an object of cultic

veneration as

a hero. This is suggested by his 'heroic' nudity, the snake in his

right hand,

and the armour, parts of which are scattered throughout the relief. The

relief

was made in the decades around the middle of the second century, but

the artist

was inspired by funerary reliefs from the Hellenistic period, the

so-called 'Heroenreliefs'.

The relief from Herodes' villa is not a funerary relief, but it may

have had a

'commemorative' function. It is an attractive suggestion that the boy

is one of

Herodes' three foster sons, all three of whom died young and for whom

Herodes

mourned as if he had lost his own children: Achilles, Memnon and

Polydeucion

(Philostratus, Lives of the Sophists 558-9).

Scholars disagree as to

whether any of the three is depicted on this relief and, if so, which

one.

Polydeucion seems at first sight the best candidate, since he is the

only

foster son of Herodes of whom we know that he became the object of a

hero cult.

However, the author of the most

recent comprehensive treatment of the relief that

I know of opts for Achilles (Jansen 2006). One of his arguments is

difficult to refute: the

boy depicted bears no resemblance to Polydeucion, of whom we have

numerous

portraits (see below for an example from the Trípoli Museum). We do not

have a

single portrait of Achilles, but the prominence of the arms would fit

well with

a deceased who had borne the name of the greatest Greek war hero before

Troy.

Relief from villa

Herodes Atticus - Photo: www.livius.org (National Archaeological

Museum,

Athens)

Relief from villa

Herodes Atticus - Photo: www.livius.org (National Archaeological

Museum,

Athens)

At the Panarcadian Archaeological

Museum in Trípoli, I photographed two objects from Herod's villa

exhibited

there: a portrait of Polydeucion ...

Polydeucion - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Tripoli)

Polydeucion - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum Tripoli)

... and a Classical (late 5th/first half 4th century BC) relief of a

young

horseman and an umpire (Spyropoulos

2006, pp. 76-78 number 14).

Classical relief from

villa Herodes Atticus - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum

Tripoli)

Classical relief from

villa Herodes Atticus - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019 (Museum

Tripoli)

For a portrait of Memnon from Herodes' villa, we

have to go to the Altes Museum in Berlin, where the below effigy of

Herodes'

black foster son ended up via the art trade. That Memnon was black we

know

thanks to Philostratus, Vita

Apollonii 3.11, who calls him an 'Ethiopian'. That

was the usual designation for blacks in ancient Greek texts. He no

doubt owed

his name to his skin colour: in Greek mythology, Memnon was king of the

Ethiopians, and as such part of the Trojan saga cycle.

Memnon, portrait bust

from the villa of Herodes Atticus, Altes Museum Berlin - Foto:

Wikimedia

Commons, José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro (CC-BY-SA-04)

Memnon, portrait bust

from the villa of Herodes Atticus, Altes Museum Berlin - Foto:

Wikimedia

Commons, José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro (CC-BY-SA-04)

Opposite

Herodes' villa, on the left-hand side of the road from Ástros to

Trípoli, is Moní Loukoús,

'one of the most enchanting monasteries in

the Peloponnese',

according to Daniel Koster.

Its existence is first documented in texts

from the 17th century, but it may be considerably older.

Founded

as

a monastery for men,

it has been inhabited and maintained by nuns since 1946. The full name

of the

monastery, Ιερά Μονή τής Μεταμορφώσεως τού Σωτήρος Χριστού, indicates

that it

is dedicated to the Transfiguration of Christ; cf. for the Orthodox

iconography

of this episode from the Gospels (Matthew 17; Mark 9; Luke 9) this

fresco in

the Serbian monastery of Gračanica in Kosovo. The unofficial name of

the monastery, 'Loukoús', is commonly associated with the Latin lucus, 'sacred

grove', but how this Greek monastery came to have a Latin nickname

remains a mystery. Perhaps

it has something to do with the fact that the monastery was for a time

in the

hands of the (Roman Catholic) Capuchin Order during the Venetian rule

of the

Peloponnese (1685-1715).

Moni Loukoús - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

Moni Loukoús - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

The

church of Moní Loukoús in its present form dates from the 17th century,

but it cannot be ruled out that it had one or more predecessors. When

the monastery was destroyed by Ibrahim Pasha's troops in 1826, the

church was spared. It is said that Ibrahim's soldiers were frightened

off by an icon of St Eustathius, which began to bleed when it was

maltreated by a soldier.

The church of Moní

Loukoús - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

The church of Moní

Loukoús - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

Building

materials from the nearby ruins of the villa of Herodes Atticus were

widely used in the construction of the church. An especially creative

solution was chosen for the suspension of the church bell.

Moní Loukoús -

Suspension of the church bell - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

Moní Loukoús -

Suspension of the church bell - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2008

To

the south-east of Moní Loukoús, there is a curious aqueduct that is

completely

covered in calcium carbonate. It dates from the Roman period and must

have supplied water

from a nearby well to Herodes' villa. A very nice series of photos

taken in autumn 2012 of both the aqueduct and the villa can be found

here.

Aqueduct south-east

of Moní Loukoús - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Aqueduct south-east

of Moní Loukoús - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

The website of the Diocese of Mantineía and Kynouría has a page with information on

the history of the monastery.

Four

kilometres east of Ástros is Parálio

Ástros ('Ástros by the Sea'). An

informative book on this town was published in 2023 by

Panayiótis Faklaris. The

nucleus of the settlement is built on the southern slope of a hill with

two peaks

jutting out into the sea (satellite photo).

On the southern peak there is a castle.

The castle of Parálio

Ástros, seen from the north - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019

The castle of Parálio

Ástros, seen from the north - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019

Faklaris dates the castle to the early 15th century and attributes it

to the Venetians, but a 17th/18th century

date (during the Venetian rule of the

Peloponnese in the decades around 1700 or the second Tourkokratía) has

also been suggested (Arvaniti 2007;

Arvaniti 2021).

When Leake

visited the site in 1806, he saw 'the remains of a modern castle' (Travels in the Morea,

volume 2, p. 484). In

1824, it came into the

possession of the three Zafirópoulos brothers, who were from the area

(Áyios

Ioánnis) and had made their fortune as merchants. Their trading company

had

branches in Ýdra, Constantinople, and Marseilles. They had returned to

their homeland

at the start of the Greek uprising of 1821, where they would play a

leading

role in the following years.

The north-western

tower of the castle of Parálio Ástros - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer 2010

The north-western

tower of the castle of Parálio Ástros - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer 2010

The castle was restored, its fortifications strengthened, and

the brothers built mansions within its walls. When Ibrahim Pasha burned

down

the villages of Kynouría in 1826, the Zafirópoulos brothers' castle

served as a

refuge for the population. It managed to withstand a direct attack by

the enemy

army. The Greek Castles

website has a page on this castle, here.

Castle of Parálio

Ástros, north-east corner - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019

Castle of Parálio

Ástros, north-east corner - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2019

On

the western, landward side of the hill, north of the

castle, the remains of an ancient wall can be seen (photo below). This

is usually associated with an Athenian attack on the Thyreátis in 424

B.C. As

we have seen above,

the Aeginetans had received permission from the Spartans to

settle in Thyréa in 431 BC, but were attacked there by an Athenian

fleet in

424 BC. According to the historian Thucydides, they were forced to

abandon a wall near the sea that they were building and to retreat to

the upper city,

which was about ten stadia (about two kilometres) from the sea

(Thucydides

4.57). The wall north of the castle is commonly identified as

Thucydides' 'wall

by the sea'.

Nisí Paralíou

Ástrous, the 'wall by the sea' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Nisí Paralíou

Ástrous, the 'wall by the sea' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Below

is a crop of a photo taken from further away but under slightly more

favourable

atmospheric conditions.

aka 'the wall of the

Aeginetans' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

aka 'the wall of the

Aeginetans' - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

The

view to the south from the hill above Parálio Ástros (photo below)

gives a good

impression of the articulation of the Kynourian coast, with its

numerous bays

and capes.

View from Nisí

Paralíou Ástrous to the south - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

View from Nisí

Paralíou Ástrous to the south - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Eight

kilometres south-west of Ástros, above the road to Ágios Pétros (satellite photo), a 630-metre high

hill stands out among the foothills of Mount Párnonas (photo below). Its

top and part of its

northern slope are surrounded by the remains of an ancient wall. The

locality

is known as Ellinikó

(Ελληνικό Άστρους), the hilltop is called Teichió (Τειχιό),

after the wall (Greek: τείχος) that is its distinctive

feature. The ruined wall is what remains of the enceinte

of an ancient fortified settlement. In 1976 and 1977 this

hill was thoroughly investigated by the Greek Settlements Seminar of

Utrecht University

(Netherlands). The settlement was measured and mapped, and the surface

remains

were carefully described. The results of this research can be found in

two

publications by Yvonne Goester: a popularising publication in volume 51

(1979) of

the journal Hermeneus (in Dutch) and the full

report (in English) in volume 1 (1993) of

the journal Pharos.

Ellinikó Ástrous -

Teichió - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Ellinikó Ástrous -

Teichió - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

The

identification of the site has been controversial, but this now seems

to have been resolved. Israel Walker (1936) believed that the main town

of northern Kynouría, Thyréa, was located here; until recently,

Fakláris was of the same opinion, but he has since abandoned this

identification. Most experts, including Pritchett, Goester and Shipley,

hold that these are the remains of Eua, a large village mentioned by

Pausanias (Description

of Greece

2.38.6). The most conspicuous remnant of the settlement is the wall,

which has a circumference of about one kilometre. Goester

argues

that the wall dates from the second half of the 4th century BC and

suggests that its construction was related to the reoccupation of the

Thyreátis by Árgos. This dating is widely accepted in

more recent literature.

From

a path running along the south-east side of the hill, remnants of

the enceinte are reasonably visible below the top (photo below).

The south-east side

of Teichió - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

The

most impressive remains of the wall, over 20 metres long and up to 3.5

metres high, are on the north side. The photo below was taken from

several hundred metres away.

Teichió, remains of

the wall on the north side - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Teichió, remains of

the wall on the north side - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Then

a section of a more recent photograph taken from roughly the same

position. The remains of the wall are in the centre of the crop.

Teichió, remains of

the wall on the north side - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015

Teichió, remains of

the wall on the north side - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2015

A few photos taken during walks around and to the top of the hill. They

illustrate the strategic location of the settlement.

View from Ellinikó

looking north-east - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

View from Ellinikó

looking north-east - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Not only was it situated high above the plain of Ástros and the Argolic

Gulf ...

The plain of Ástros,

Parálio Ástros, and the Argolic Gulf as seen from Ellinikó - Photo:

Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2015

The plain of Ástros,

Parálio Ástros, and the Argolic Gulf as seen from Ellinikó - Photo:

Jaap-Jan

Flinterman, summer 2015

...

it also controlled the land roads north to the central massif

of Mount Párnonas, leading to the central and southern Peloponnese, to

Tegea and Sparta.

View from Ellenikó

looking south-west - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

View from Ellenikó

looking south-west - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

Climbing

up the hill along a goat track on the north-east side, you pass the

enceinte at its northeasternmost point. This is tower no. 1 (pictured

below) in Goester's numbering system. Goester 1993 gives a

comprehensive

and informative description of the site.

Teichió, the northeasternmost

point of the enceinte - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Teichió, the northeasternmost

point of the enceinte - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

About

25 metres to the west is tower no. 2 (pictured below), from which the

continuous section of well-preserved wall visible in the photo above

begins.

Teichió, Tower no. 2

Goester - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Teichió, Tower no. 2

Goester - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

On the inside, the ground level reaches the top of the wall (photo

below), and although the photo above

makes it look easy to approach the wall from the outside, in practice

it is quite difficult due to the nature of the terrain.

The

wall on the north side seen from above -

Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

The

wall on the north side seen from above -

Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

The

photo below was therefore taken from tower no. 2. Incidentally, this

and two other photos of Ellinikó are by Mieke Prent and Stuart MacVeagh

Thorne, who, as archaeologists, made better photographic

choices than I

did at Teichió.

The wall on the north

side seen from tower 2 - Photo: Mieke Prent, summer 2017

The wall on the north

side seen from tower 2 - Photo: Mieke Prent, summer 2017

The wall was defended by eleven towers. The main function of these towers was to expose those attacking the wall

to flanking fire. An alternative, more economical device for achieving

the same objective was the 'indented trace', i.e. the construction

of the wall 'in staggered sections of short flank walls at right angles

to each section of the face of the curtain' (Scranton 1941). At

Elliniko this device was used to the west of tower no. 3, i.e. to the west of the continuous section of

well-preserved wall pictured above. Here we find five short flank walls

('jogs').

Jog to the west of tower no. 3 - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

Jog to the west of tower no. 3 - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

To

the southwest, the hill is connected by a saddle to another hill almost

as high. To compensate for this defensive weakness, the enceinte at

this point was fortified with a triangular bastion (tower 6). This is

the most sophisticated piece of military architecture found at Teichió.

Below are four photographs of this bastion. The first shows the bastion

from a position inside the wall. On the top left are the peaks of

the central massif of the Párnonas.

Teichió, southwestern

bastion - Photo: Mieke Prent, summer 2017

Teichió, southwestern

bastion - Photo: Mieke Prent, summer 2017

The

second is from the remains of the wall to the north of the bastion. The

picture shows how the wall was constructed: two shells of hewn and

stacked blocks with a filling of loose rock.

Teichió, southwestern

bastion - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

Teichió, southwestern

bastion - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2017

The third shows the bastion from a position outside the wall.

Teichió, the

south-western bastion from outside the wall - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman,

September 2023

Teichió, the

south-western bastion from outside the wall - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman,

September 2023

The fourth shows that the stones here are more regularly hewn and

jointed than elsewhere in the enceinte.

Teichió, northern

wall of the south-western bastion - Photo: Stuart MacVeagh Thorne,

summer 2017

Teichió, northern

wall of the south-western bastion - Photo: Stuart MacVeagh Thorne,

summer 2017

The fact that one part of a fortification is built in a more

regular way than the rest of it may give rise to the suspicion that it

is a later addition. Goester thinks that

the different style of masonry in tower 6 is not in itself an argument

for dating this part of the fortification later. Balandier and

Guintrand

(2019), on the other hand, argue that the south-west bastion must be an

addition from the middle of the third century BC. Perhaps future

excavations will clarify the matter. In the meantime, a possible

re-inforcement of the south-western part of the enceinte with a

bastion, about the middle of the third century, does not really affect

the arguments for a dating of the present perimeter to the late fourth

century BC.

Approximately

700 metres north-north-east of Teichió, at a place known locally as

Anemómylos, is a structure built in 1960 as a makeshift shelter, the

roof of which has since collapsed.

Anemómylos - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Anemómylos - Photo:

Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2011

Its lower part consists of the well-preserved remains of an ancient

building measuring just under ten by six metres.

... the

well-preserved remains of an ancient building ... - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman,

summer 2011

... the

well-preserved remains of an ancient building ... - Photo: Jaap-Jan

Flinterman,

summer 2011

It was probably a small temple, constructed from carefully hewn

limestone blocks, visible on both the exterior ...

Anemómylos, western

half of the south wall of the temple - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer 2011

Anemómylos, western

half of the south wall of the temple - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer 2011

...

and the interior. Fakláris dates the temple to the second half of the

fourth century BC. More photos of the small building can be found on

this page of the German-language

website www.argolis.de.

Anemómylos, inner

side of the northern wall of the temple - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer

2011

Anemómylos, inner

side of the northern wall of the temple - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman,

summer

2011

If

Eua was indeed located on Teichió, this building could well have been a

temple to the healing deity Polemocrates (cf. Gorrini 2014). According

to Pausanias (Description

of Greece

2.38.6), there was a sanctuary at Eua for this healing demigod, who was

considered to be a grandson of Asclepius. Near the remains of the

temple, in the 1960s, a tile stamp was found with the text ΕΥΑΤΑΝ

ΔΑΜΟΣΙΟΙ, i.e. ΕΥΑΤΑΝ (ΚΕΡΑΜΟΙ) ΔΑΜΟΣΙΟΙ, 'roof tiles of the citizens

of Eua' (something like 'municipal roof tiles'). At the beginning of

this century, another roof tile (stamp) with this text surfaced,

finally settling the debate on the identification of Teichió in favour

of Eua. In the words of the 2009

publication

by Grigoris Grigorakakis

reporting the discovery of the second tile: 'The identification of

Teichió with ancient Eva is considered certain, since two stamped tiles

from it bear the ethnic ΕΥΑΤΑΝ.'

In some places the

hill is littered with sherds - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

In some places the

hill is littered with sherds - Photo: Jaap-Jan Flinterman, summer 2010

We noted above

that in 338 BC Argos was confirmed in its possession of the Thyreátis

by the Macedonian king Philip II. It is likely that the region had

already become disputed territory in the preceding decades. Shortly

after the turn of the century, a collection of about 135 inscribed

bronze tablets was found in Argos. The texts date from the first half

of the fourth century BC. They are financial records of the temple

treasure of Pallas Athena, which also functioned as a 'state bank'. As

far as I know, the texts have not yet been published, but they have

been reported (Kritzas 2006;

Kritzas 2013). These

records mention places in the

Thyreátis such as Neris and Eua as villages under Argos. In 371 BC, the

Spartans suffered a devastating defeat at Leuctra in central Greece at

the hands of the Thebans under Epaminondas. This defeat marked the end

of undisputed Spartan hegemony in the Peloponnese. The new documents

from Argos indicate that after the Battle of Leuctra, Argos managed to

regain possession of the Thyreátis, at least temporarily.

Presumably,

Argos and Sparta were not the only interested parties (for the content

of this and the following paragraph, see Nielsen

2002 and Roy 2009).

The geographical lexicon (E 145 Billerbeck) of Stephanus of Byzantium

(6th

century AD) calls Eua a πόλις Ἀρκαδίας, a 'city of Arcadia'.

The Byzantine geographer relies for this information on a 4th-century

BC historian, Theopompus of Chios (FGrHist

115F60). More specifically, Stephanus claims to have taken the

information about Eua from the sixth book of Theopompus' Philippica. The

work of Theopompus is lost except for fragments like this one, but we

do know that in Book 6 of his Philippica

he dealt with the history of the years 354-353 BC. Apparently, in those

years, there was reason to call Eua an 'Arcadian city'. By 370 BC,

Arcadian cities and tribal communities in the central Peloponnese had

united in a confederation to take maximum advantage of the end of

Spartan hegemony, and in the following years, regions outside the

Arcadian core area had been incorporated into this confederation. It is

not inconceivable that the Arcadians attempted to do the same with the

Thyreátis. The existence of an Arcadian claim to the Thyreátis is also

supported by the existence of a mythical genealogy mentioned by

Pausanias (Description

of Greece

8.3.3). According to this genealogy, one of the sons of the Arcadian