Is the Sage the Sophist's Mouthpiece?

Political Interpretations of Philostratus' Life of Apollonius

Corpus Christi Classical

Seminar, Oxford 8 February 1995

This

is the text of a talk for the Corpus Christi Classical Seminar in

February 1995. It was essentially a viva voce prepublication of the

final section of the fourth chapter of my Power, Paideia

& Pythagoreanism, that at the time was being

translated by Peter Mason, who also corrected the English of this

paper.

Introduction

Political

interpretations of Philostratus' Life of

Apollonius:

a survey

Political

interpretations of Philostratus' Life

of Apollonius: four objections

Allusions

to the

Severan period in the Life

of Apollonius

Concluding remarks

Titles

mentioned

Introduction

In a footnote to a major

article, published in 1978, on the traditions concerning

Apollonius of

Tyana

and on Philostratus' romanticized biography of this first century

Pythagorean

philosopher and miracle worker, Ewen

Bowie referred to a couple of

publications which contained an interpretation of Philostratus' Life of

Apollonius

as a politically tendentious piece of writing: an 1889

dissertation by a young German, Johannes

Göttsching, and an article

published

in 1941 by the Italian scholar Aristide Calderini. Bowie

briefly

dismissed

the thesis defended by Calderini, but he saw "some

plausibility

in

Göttsching's arguments, though they cannot be taken so far as

Göttsching

wishes." Today's talk may be considered an elaboration of

Ewen Bowie's footnote. What I intend to do is the following. In the

first

place, I shall present a survey of what, for brevity's sake, I have

labelled 'political

interpretations' of Philostratus' Life

of Apollonius, starting with Göttsching's

dissertation and following the trail up to the 1980's. Secondly, I

shall point

out what are, in my opinion, four objections to these

interpretations. In the

third place I shall try to formulate some criteria which should be

followed in

tracking down allusions to the author's lifetime, the Severan period,

in the Life

of Apollonius, and I shall present and discuss the results

of the application

of these criteria. Some concluding remarks will round off this talk.

Before I make a start with the implementation of this programme,

however, three preliminary points should be brought up. Firstly, we

should

recognize that political interpretations of Philostratus' Life of

Apollonius are very tempting indeed, given both the

biography of the author

and the contents of the work.  Philostratus was a member of a family

which

belonged to the upper echelons of the Athenian citizen body and which

produced

members of the senatorial order in the next generation. He was

probably a

member of the Athenian council and held the position of hoplite general

in that

city in the first decade of the third century. Moreover, for some ten

years he

was a protégé of Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus and the

mother of

his successor Caracalla. The

Life of Apollonius itself was

commissioned by the empress, although it was completed after her death

in 217.

Philostratus' other major work, the Lives of the sophists,

was dedicated

to the proconsul of Africa, Gordian senior, in the winter of

237/238. As for the contents of

the Life of Apollonius,

even a cursory reading is sufficient to convey

the impression that the protagonist is a philosopher involved in

politics, a

man who intervenes in civic conflicts and who establishes relations of

varying

cordiality with several first-century emperors, among them Vespasian,

Titus and

Domitian. Besides, even students familiar with imperial Greek

literature will

be struck by the presence of a very pronounced sense of Greek

superiority in

the Life.

At first sight, therefore, the search for a political tenor

in the Life of

Apollonius

does not seem too far-fetched.

Philostratus was a member of a family

which

belonged to the upper echelons of the Athenian citizen body and which

produced

members of the senatorial order in the next generation. He was

probably a

member of the Athenian council and held the position of hoplite general

in that

city in the first decade of the third century. Moreover, for some ten

years he

was a protégé of Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus and the

mother of

his successor Caracalla. The

Life of Apollonius itself was

commissioned by the empress, although it was completed after her death

in 217.

Philostratus' other major work, the Lives of the sophists,

was dedicated

to the proconsul of Africa, Gordian senior, in the winter of

237/238. As for the contents of

the Life of Apollonius,

even a cursory reading is sufficient to convey

the impression that the protagonist is a philosopher involved in

politics, a

man who intervenes in civic conflicts and who establishes relations of

varying

cordiality with several first-century emperors, among them Vespasian,

Titus and

Domitian. Besides, even students familiar with imperial Greek

literature will

be struck by the presence of a very pronounced sense of Greek

superiority in

the Life.

At first sight, therefore, the search for a political tenor

in the Life of

Apollonius

does not seem too far-fetched.

The second preliminary point I want to bring up concerns

the meaning of a few words which, until now, I have used rather

uncritically.

What is a politically tendentious piece of writing? When do I classify

the

interpretation of a literary work as 'political'? I have to admit that

an

attempt to answer these questions on the level of literary theory is

beyond my

capabilities as a historian. Therefore, I shall confine myself to a

somewhat

less ambitious undertaking and offer you a preliminary inventory of

the main

characteristics of the interpretations of the Life of Apollonius

that

I have labelled political. We are dealing with a text about a

first-century

figure who had been dead for more than hundred years, when his

biographer

reached maturity. Consequently, the first condition that political

interpretations

of the Life of

Apollonius have to meet is a willingness on the part of

their defenders to perceive a substantial number of allusions to early

third-century situations and events in a narrative set in the first

century.

Naturally, one should distinguish an unintentional anachronism from a

deliberate

allusion. The second characteristic of the interpretations under

discussion

is, therefore, a willingness on the part of their advocates to argue

that such

allusions have been included by Philostratus with the intention of

drawing the

attention of his readers to certain events and situations. The most

sweeping

political interpretations of the

Life of Apollonius thus consider substantial

parts of the text to reflect Philostratus' opinions on issues ranging

from

relations inside the imperial family to foreign and military policies

and from

taxation to socio-political life in Greek cities. Moreover, they

envisage the

act of writing the text as a conscious effort to convey these

opinions to an

intended readership. If such interpretations are valid, we may,

without

further ado, consider the

Life of Apollonius

a politically tendentious

piece of writing.

There are, however, less far-reaching forms of the same

approach. For example, the position of the alleged allusions in the

narrative

may range from central to marginal. Thus some interpreters may look

upon the

characterisation in action and speech of the protagonist or other

important

characters as reflecting Philostratus' views on contemporary

socio-political

reality, while others regard only a couple of minor anecdotes or

remarks as

possibly significant. Moreover, interpreters may confine themselves

to the

proposition that the alleged allusions to early third-century events

and situations

betray an awareness on the part of Philostratus of such events and

situations,

without suggesting that the Athenian sophist wanted to convey a

specific

message to the readers of his Life

of Apollonius. For the moment, I want

to include these less far-reaching interpretations in my enquiry, but

it should

be obvious that I do not disregard the differences between such

interpretations

and the interpretation of the Life

as politically tendentious in the

proper sense of the word.

My third and last preliminary point is a warning. Perhaps

some of the older interpretations which will pass in review will

strike you as

either far-fetched or outdated or both. None the less, my aim is not to

entertain you with some curiosities from the past of classical

scholarship nor

to score easy victories over convenient whipping-boys. On the

contrary, by

uncovering and discussing the assumptions of these interpretations

and by

presenting my objections to them, I hope to sharpen our insight into

the

presuppositions on which more fashionable readings - including my

own - are founded. The extent to which I have succeeded will, in

other words, become apparent from your willingness to criticise the

assumptions

in the second and third parts of my talk, dealing with the

objections to

political interpretations and with what I consider allusions to

contemporary

events and situations in the

Life of Apollonius.

Political

interpretations of Philostratus' Life of

Apollonius:

a survey

So much for my

preliminary points. I shall now present a brief survey of political

interpretations

of the Life of Apollonius

which have been proposed during the last

hundred years. The

first of these, defended by Johannes

Göttsching in

his 1889

dissertation ,

certainly falls within the limits of political

interpretations

in the proper sense of the word. Göttsching claimed that with the

establishment

of the Severan dynasty the imperial power had passed into the hands of

African

and Asiatic barbarians. In reaction to this development, which was

lamented

by traditionally-minded Romans and cultured Greeks alike, Philostratus

assigned his hero the role of 'Herold des Hellenismus', 'herald of

Hellenism'. According to Göttsching, the stark contrast

between

Hellenic

virtues and barbarian vices that is to be found in the Life should be

read in this light. Göttsching also claimed to be able to detect

numerous

allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors. Thus he believed

that the

descriptions of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian and their mutual

relations

presented Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla in disguise, while

Philostratus'

portrait of Nero stood for that of Elagabalus. Assuming that the

writer would

not have dared to publish a work of this kind during the reign of

Elagabalus,

so that the Life

could not have been issued before the reign of Severus

Alexander, Göttsching formulated the hypothesis that at least one of

Philostratus' intentions was to advise the young emperor by means of

the

explicit recommendations and the positive and negative examples of

monarchical

behaviour contained in the

Life of Apollonius.

,

certainly falls within the limits of political

interpretations

in the proper sense of the word. Göttsching claimed that with the

establishment

of the Severan dynasty the imperial power had passed into the hands of

African

and Asiatic barbarians. In reaction to this development, which was

lamented

by traditionally-minded Romans and cultured Greeks alike, Philostratus

assigned his hero the role of 'Herold des Hellenismus', 'herald of

Hellenism'. According to Göttsching, the stark contrast

between

Hellenic

virtues and barbarian vices that is to be found in the Life should be

read in this light. Göttsching also claimed to be able to detect

numerous

allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors. Thus he believed

that the

descriptions of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian and their mutual

relations

presented Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla in disguise, while

Philostratus'

portrait of Nero stood for that of Elagabalus. Assuming that the

writer would

not have dared to publish a work of this kind during the reign of

Elagabalus,

so that the Life

could not have been issued before the reign of Severus

Alexander, Göttsching formulated the hypothesis that at least one of

Philostratus' intentions was to advise the young emperor by means of

the

explicit recommendations and the positive and negative examples of

monarchical

behaviour contained in the

Life of Apollonius.

Göttsching's ability to recognise allusions to the

Severan emperors is very great, so a couple of examples must be enough

to

illustrate his method. In book 4 chapter 22,

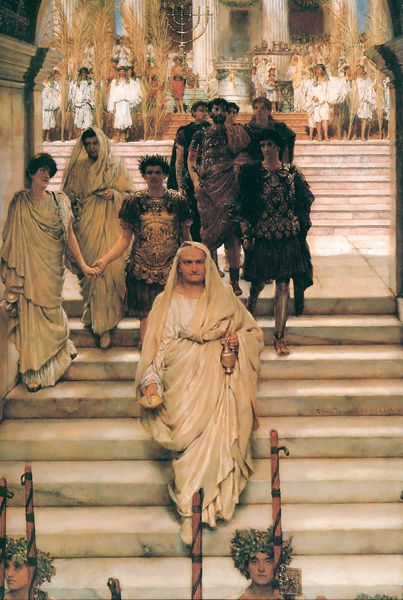

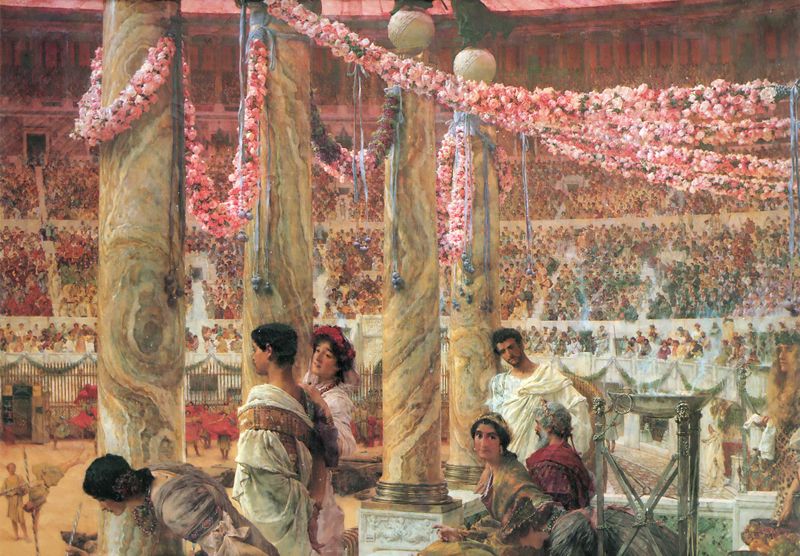

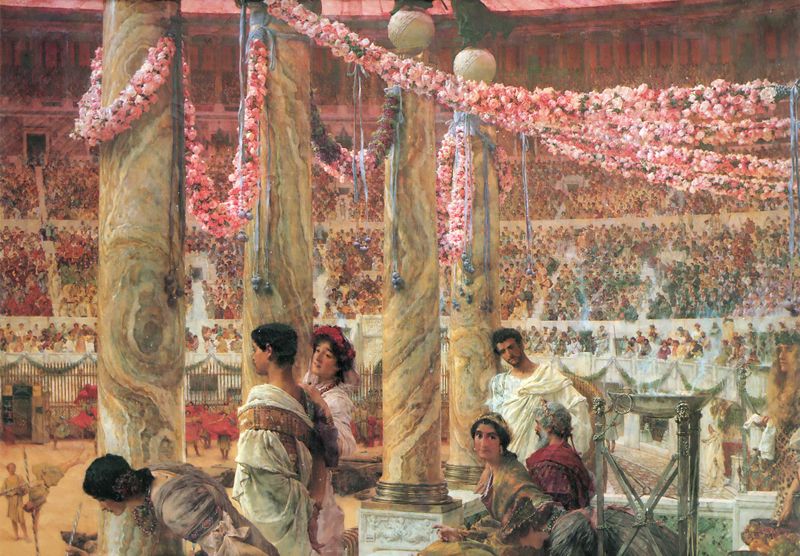

Apollonius rebukes the Athenians for watching gladiatorial games in

the theatre

of Dionysus. Göttsching refers to Cassius Dio (77.6.2) for

Caracalla's enthusiasm

for such spectacles and suggests that the rebuke of Philostratus'

Apollonius

should be understood as in fact aimed at Caracalla. In book 6 chapter

32, Philostratus reports that Titus was poisoned by Domitian.

Göttsching

points out that Geta was murdered by Caracalla and claims that the

relation

between the Flavian brothers, as described by Philostratus, refers to

the

Severan brothers.

A second scholar who

interpreted the portrayal of the

Flavian emperors by Philostratus as a complex of deliberate

allusions to

Septimius Severus and his sons and who claimed that the Life of Apollonius

contained an explicit message for a specific addressee was Aristide

Calderini,

who

also proposed a new dating of the Life. According

to

Calderini, the

Life of Apollonius - or at least a first version of the

work - was not completed after Julia Domna's death in 217, but in

the years between 202 and 205, between the author's arrival in Rome and

the death of

Plautianus. The main argument adduced by

Calderini for this claim is

the fact

that Philostratus repeatedly makes mention of the disastrous effect

of bad

counsellors and informers on emperors; in this connection Calderini

referred,

among other passages, to book 8, chapter 7, section 16 (section 50 in

Jones' Loeb), the

peroration of the speech in his defence which Apollonius, according to

Philostratus,

had written for his trial before Domitian. Such passages, Calderini

claimed,

were intended to warn Septimius Severus of the praefectus praetorio

Plautianus,

and Philostratus functioned as a political instrument in Julia

Domna's

struggle against the influential prefect. On the basis of this

hypothesis,

Calderini postulated the death of Plautianus as the terminus ante

quem for

the composition of the first version of the Life. He then

proceeded to

find further support for this hypothesis. For example, he interpreted

the

encomium of the harmonious participation of young and old in political

power

which Philostratus puts in the mouth of Apollonius before

Titus (VA

6.30), as

an allusion to the position of Caracalla as co-regent of Septimius

Severus. The report that Vespasian was sixty years old in 69

(VA 5.29) referred,

according to the Italian scholar, to the age Septimius Severus was to

reach in

206.

who

also proposed a new dating of the Life. According

to

Calderini, the

Life of Apollonius - or at least a first version of the

work - was not completed after Julia Domna's death in 217, but in

the years between 202 and 205, between the author's arrival in Rome and

the death of

Plautianus. The main argument adduced by

Calderini for this claim is

the fact

that Philostratus repeatedly makes mention of the disastrous effect

of bad

counsellors and informers on emperors; in this connection Calderini

referred,

among other passages, to book 8, chapter 7, section 16 (section 50 in

Jones' Loeb), the

peroration of the speech in his defence which Apollonius, according to

Philostratus,

had written for his trial before Domitian. Such passages, Calderini

claimed,

were intended to warn Septimius Severus of the praefectus praetorio

Plautianus,

and Philostratus functioned as a political instrument in Julia

Domna's

struggle against the influential prefect. On the basis of this

hypothesis,

Calderini postulated the death of Plautianus as the terminus ante

quem for

the composition of the first version of the Life. He then

proceeded to

find further support for this hypothesis. For example, he interpreted

the

encomium of the harmonious participation of young and old in political

power

which Philostratus puts in the mouth of Apollonius before

Titus (VA

6.30), as

an allusion to the position of Caracalla as co-regent of Septimius

Severus. The report that Vespasian was sixty years old in 69

(VA 5.29) referred,

according to the Italian scholar, to the age Septimius Severus was to

reach in

206.

A

third attempt to interpret part of the Life of

Apollonius in terms of relations in the Severan

court was

undertaken by

Friedrich Lenz, in an

article published in 1964. Lenz'

reasoning, at

least in

this article, is not particularly convincing, and there would

not be

any reason

to rescue this publication from a well-deserved oblivion, were it not

for the

fact that Lenz named Caracalla as the addressee of a hidden message in

the Life

of Apollonius, thus bringing the number of

alleged

addressees of

Philostratus' work in the Severan family to three.

A Marxist version of

the interpretation of the Life

of

Apollonius as a politically tendentious piece of writing

was produced

by

the Russian scholar Elena

Schtajerman in a work first published in

1957, The

crisis of slave society in the western half of the Roman empire.

I have

consulted the German translation, published in 1964. Schtajerman's

book

contains a long chapter on the political programmes and ideological

currents of

the early third century, which assigns a prominent place to

Philostratus' Life

of Apollonius. She regards the Greek

intellectuals who

surrounded Julia

Domna as representatives of an intelligentsia which was closely

connected with

the municipal aristocracy.  As

a result of the decline of the cities,

this

intelligentsia became increasingly dependent on the provincial

aristocracy, a

dependency which was accompanied by feelings of hostility on the part

of

clients towards their patrons. The imperial bureaucracy offered a way

out of this

dependency. However, Caracalla objected to sophists and other

representatives

of the intelligentsia. At the instigation of Julia Domna, who

disagreed with

her son on this score, Philostratus addressed his Life of Apollonius

to

the municipal aristocracy with a political programme that reflected the

interests and views of this aristocracy. His political ideal was an

empire, as

it had been in the Antonine period, founded on a smoothly functioning

urban

self-government. This ideal implied respect for the rights of the

social elite

in the cities; at the same time, it demanded that the members of this

elite

should not evade their obligations and should allow the rest of the

citizen

body to share to some extent in their possessions in order to

guarantee social

harmony. The implementation of this ideal was to be guaranteed by a

strong

imperial authority, which must neither degenerate into tyranny, nor be

dependent on the representative body of the provincial aristocracy,

the

senate. As regards foreign policy, the municipal aristocracy, unlike

the

provincial aristocracy, advocated a policy of peace: plans of conquest

should

be abandoned and war should be avoided at all costs.

As

a result of the decline of the cities,

this

intelligentsia became increasingly dependent on the provincial

aristocracy, a

dependency which was accompanied by feelings of hostility on the part

of

clients towards their patrons. The imperial bureaucracy offered a way

out of this

dependency. However, Caracalla objected to sophists and other

representatives

of the intelligentsia. At the instigation of Julia Domna, who

disagreed with

her son on this score, Philostratus addressed his Life of Apollonius

to

the municipal aristocracy with a political programme that reflected the

interests and views of this aristocracy. His political ideal was an

empire, as

it had been in the Antonine period, founded on a smoothly functioning

urban

self-government. This ideal implied respect for the rights of the

social elite

in the cities; at the same time, it demanded that the members of this

elite

should not evade their obligations and should allow the rest of the

citizen

body to share to some extent in their possessions in order to

guarantee social

harmony. The implementation of this ideal was to be guaranteed by a

strong

imperial authority, which must neither degenerate into tyranny, nor be

dependent on the representative body of the provincial aristocracy,

the

senate. As regards foreign policy, the municipal aristocracy, unlike

the

provincial aristocracy, advocated a policy of peace: plans of conquest

should

be abandoned and war should be avoided at all costs.

In certain respects, Schtajerman's treatment of the Life

has to be distinguished from the interpretations by Göttsching,

Calderini and

Lenz. The Soviet scholar did not claim that the Life of Apollonius

was

addressed to a member of the imperial family; in her view,

Philostratus' work

was addressed to the urban elites of the Roman empire. As a result, she

was less

fixated on the episodes involving emperors in the Life and paid more

attention to those episodes in which the protagonist intervenes in the

socio-political life of cities. Nevertheless, she did interpret the

Life

as the packaging of a political programme and the main character as

the author's

mouthpiece. For instance, she claimed to detect a clear preference for

dynastic succession above adoption in the Life. In this

connection,

she referred to the meeting between Apollonius and Vespasian in

Alexandria, as

described in book 5 (chapters 28 and 35). The

activities and

speeches of Philostratus' Apollonius in Greek cities reflected, in her

opinion,

the views of the author of the Life

on the problems of civic life in

the

Severan period.

In the 1970s and 1980s,

bourgeois scholars again took over the torch. Both Geza Alföldy, in an

article

published in Greek,

Roman and Byzantine Studies of 1974 and Lukas de

Blois in his inaugural lecture of 1981 (published in Historia in 1984)

used the Life of

Apollonius as evidence for the perception of the

onset of the third-century crisis by contemporary Greek authors.

Alföldy and

De Blois especially referred to book 5 chapter 36, a speech of

Apollonius

before Vespasian containing recommendations on the exercise of

imperial power.

In this speech, whose contemporary relevance had already been stressed

by

Schtajerman, the emperor is advised to moderate the tax burden, to use

his

absolute power wisely, to respect the law, to honour the gods, to keep

his sons

properly under control, to curb the extravagance of the imperial slaves

and

freedmen, etc. Alföldy considered this speech, together with the

Maecenas

speech in book 52 of the Roman

History of Cassius Dio, an expression of

the author's conviction "that, in spite of all present evil,

the sound

world of the past could be restored." De Blois referred to

the advice

of Philostratus' Apollonius to moderate the tax burden as one of

several

examples to illustrate the frequency of complaints on this score among

Greek

authors of the first half of the third century - complaints that

were often combined with expressions of dissatisfaction at the amounts

of

money squandered on the military.

There are important differences between the approach of

Göttsching, Calderini, Lenz and Schtajerman, on the one hand, and the

utilization of Philostratus by Alföldy and De Blois, on the other.

Neither

Alföldy nor De Blois claimed that Philostratus tried to convince an

intended

readership of the views contained in Apollonius' speech to Vespasian,

nor did

they explicitly label the

Life a politically tendentious piece of

writing. They did suggest, however, that the recommendations of the

main

character of the Life

of Apollonius are evidence of a 'consciousness

of crisis' - a

Krisenbewusstsein in Alföldy's phrasing -

on the part of the author. In their opinion, the speech of Apollonius

bears

witness to the perception of early third-century socio-political

reality by

Philostratus as well as to the remedies that the Athenian sophist

envisaged

for contemporary ills. In all fairness I should add that Philostratus'

work is

not central to their respective arguments. Of the witnesses adduced by

Alföldy

and De Blois, other authors, for example historiographers such as

Cassius Dio

and Herodian and orators such as the author of the Eis basilea, a

mid third-century encomium, play a much more important part.

Nevertheless,

Alföldy and De Blois do make assumptions about Philostratus'

perception of the

situation of the Roman empire in the first half of the third century,

and these assumptions should be

stated and examined with the same rigour as the more sweeping

suppositions of

scholars who offer a full-blown political interpretation of the Life of

Apollonius.

Political

interpretations of Philostratus' Life

of Apollonius: four objections

The

arguments presented

in favour of political interpretations of the Life of Apollonius

have

generally met with a degree of scepticism. Göttsching's ideas were

almost

immediately dismissed in a review by J. Miller, and Emilio

Gabba

refuted Calderini's hypothesis in an appendix to an article on Cassius

Dio, published

in 1955. Moreover, Friedrich

Solmsen and Jonas Palm

criticized the

search for a

contemporary political tenor in general. Graham

Anderson too, in his

monograph

on Philostratus, has made pertinent observations on this score. In

passing,

these scholars mentioned several fundamental objections to political

interpretations of the Life,

without, however, going into a full

consideration of the subject.

What are the main objections to the interpretations that

have passed in review until now? In the first place, scholars like

Göttsching,

Calderini and Schtajerman have neglected the fact that Philostratus

must have

taken considerable pains in outlining the historical background to

the alleged

activities of his hero. In my opinion, there can be no doubt that the

sophist

drew heavily on imperial biography and historiography on the Roman

empire in the first century. I

should add that this holds true regardless of the question as to

whether he

found some indications for contacts of Apollonius with emperors in

traditions

directly connected with the Tyanean sage. Even where Philostratus had

access

to such traditions, he elaborated them with material taken from

imperial

biographical and historiographical sources. The results of his efforts

are

quite respectable, in spite of some chronological mistakes and

historical

improbabilities.

I

should add that this holds true regardless of the question as to

whether he

found some indications for contacts of Apollonius with emperors in

traditions

directly connected with the Tyanean sage. Even where Philostratus had

access

to such traditions, he elaborated them with material taken from

imperial

biographical and historiographical sources. The results of his efforts

are

quite respectable, in spite of some chronological mistakes and

historical

improbabilities.

Let me

try to illustrate

the consequences of this observation. We have seen that Calderini took

the

report that Vespasian was sixty years old when he came to power as an

allusion

to the age that Septimius Severus was to reach in 206. Tacitus'

Histories

(2.74.2 and 5.8.4),

however, show that Vespasian's age played a part in discussions

during the

establishment of the Flavian dynasty. The same is

true of

the emphasis on dynastic succession that Schtajerman noticed in

Philostratus'

description of the alleged meeting between Apollonius and Vespasian and

that

she interpreted as the expression of the Athenian sophist's opinion.

Again,

dynastic continuity was an important topic in the historiography on the

first

years of the Flavian regime, as can be seen from Tacitus' Histories

(4.52.1) and Josephus' Jewish

war (4.596). The references to the disastrous effects of

the activities of informers, according to Calderini intended as a

warning to

Septimius Severus of the influence of Plautianus, are nothing more than

an

authentic touch in Philostratus' portrait of Domitian. The

activities of

informers under the last Flavian emperor are highlighted by Pliny

(Panegyricus

35.2).

As for Göttsching's view that Apollonius' prophecy of the poisoning of

Titus

by Domitian was an allusion to Geta's death at the hand of his brother

Caracalla,

we should note that Cassius Dio (66.26.2) held Domitian responsible

for Titus'

death,

although he does not mention poison in this connection. The

first

reference to poisoning in the extant literature is not found until the

fourth

century, in Aurelius Victor (Caesares

10.5 and 11.1). It does not seem implausible,

however,

that rumours of poisoning had already found expression in

second-century

literary versions of Titus' death. The development of the tradition on

the

death of Titus and Domitian's alleged part in it were overlooked by

Göttsching.

I realise, of course, that a reference to a first-century

event by Philostratus, even if he found it in historiography or

imperial

biography, can still have been understood by his contemporaries as an

allusion

to a third-century event. Such a reading can even have been intended

by

Philostratus himself. The report of Titus' death and of Domitian's

part in it

may be a case in point. Interestingly, Herodian (4.5.6) has

Caracalla, in his

defence

before the senate after the liquidation of Geta ,

refer to earlier

instances of

emperors having eliminated their brothers, explicitly citing the case

of

Domitian and Titus. However, by reckoning with the

probability that

Philostratus did a quite respectable amount of homework for his

portraits of

first-century emperors, we can eliminate at least a number of the more

far-fetched interpretations of passages in the Life as allusions.

Moreover, if the observation that in drawing his imperial portraits

Philostratus used imperial biography and historiography on the first

century

on a considerable scale is correct, it belies the assumption that he

systematically attempted to fit the characterisation of first century

emperors

into a third-century mould. Once again, this does not exclude the

possibility

of allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors, but such

allusions, if

they can be made plausible, have a much more incidental character than

was

suggested by scholars such as Göttsching, Calderini and Schtajerman.

,

refer to earlier

instances of

emperors having eliminated their brothers, explicitly citing the case

of

Domitian and Titus. However, by reckoning with the

probability that

Philostratus did a quite respectable amount of homework for his

portraits of

first-century emperors, we can eliminate at least a number of the more

far-fetched interpretations of passages in the Life as allusions.

Moreover, if the observation that in drawing his imperial portraits

Philostratus used imperial biography and historiography on the first

century

on a considerable scale is correct, it belies the assumption that he

systematically attempted to fit the characterisation of first century

emperors

into a third-century mould. Once again, this does not exclude the

possibility

of allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors, but such

allusions, if

they can be made plausible, have a much more incidental character than

was

suggested by scholars such as Göttsching, Calderini and Schtajerman.

The second objection to political interpretations is the

commonplace, not to say hackneyed character of most of the

recommendations on

political topics that the main character of the Life of Apollonius

expresses, especially in his speech to Vespasian on the exercise of

autocracy

in book 5 chapter 36. With one exception - to which I shall return

presently - I can find nothing in this

speech that could not have

been written around 100 A.D. and much that could have been written -

and in fact was written - in any speech on kingship from

the fourth century B.C. onwards. Consider, for example, the

recommendation to

moderate the tax burden (VA

5.36). In other third-century authors,

statements

on the tax burden are directly linked to the problem of the demands

made by the

military, as in Cassius Dio (77.10.4) and the speech

Regarding

the emperor ([Aristides], or.

35.30); the

relevance to the first half of the third century of

utterances

that stress the connection between the costs of the armies and the tax

burden

goes without saying. In the

Life of Apollonius, this link is notably

absent. The admonition to help the needy and guarantee the rich the

safe

enjoyment of their wealth seems to be simply an elaboration of a

standard

ingredient of manuals on royalty, and I fail to see any special

indication

pointing to the early third century, as De Blois does. Two

very similar

pieces

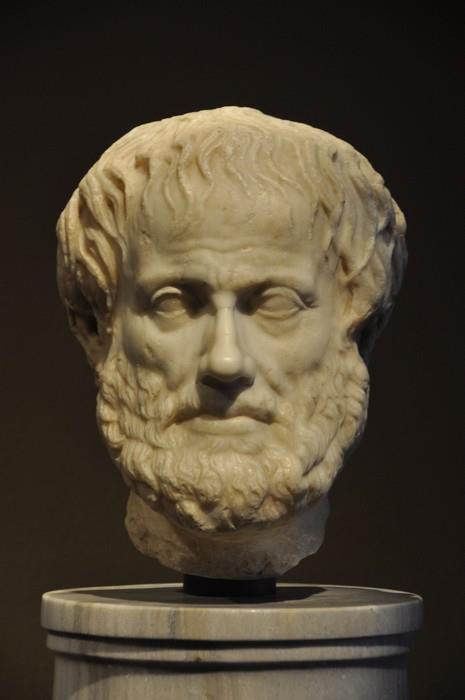

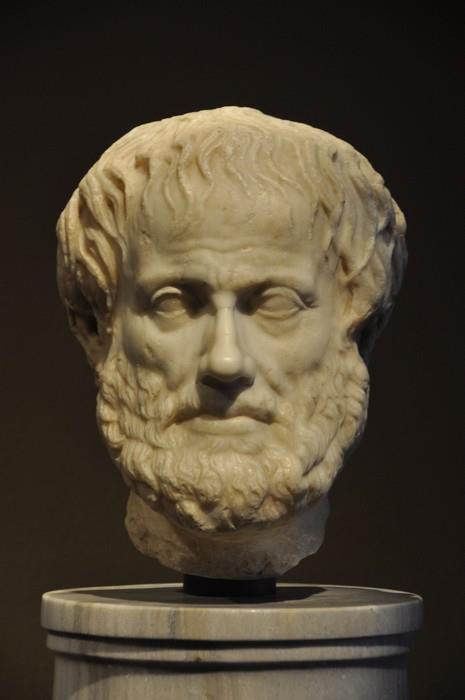

of advice from the fourth century B.C. can be found in Isocrates and

Aristotle.

Isocrates (Ep.

7.4) preaches to Timotheus of Heraclea the usual respect for the

possessions

of the rich, while Aristotle (Politica 5

1310b40-1311a2) states that the

king ensures that neither

the

wealthy nor the mass of the people suffer injustice - a

clear

parallel with the policy of running with the hare and hunting with the

hounds

advised by Philostratus' Apollonius.

- I can find nothing in this

speech that could not have

been written around 100 A.D. and much that could have been written -

and in fact was written - in any speech on kingship from

the fourth century B.C. onwards. Consider, for example, the

recommendation to

moderate the tax burden (VA

5.36). In other third-century authors,

statements

on the tax burden are directly linked to the problem of the demands

made by the

military, as in Cassius Dio (77.10.4) and the speech

Regarding

the emperor ([Aristides], or.

35.30); the

relevance to the first half of the third century of

utterances

that stress the connection between the costs of the armies and the tax

burden

goes without saying. In the

Life of Apollonius, this link is notably

absent. The admonition to help the needy and guarantee the rich the

safe

enjoyment of their wealth seems to be simply an elaboration of a

standard

ingredient of manuals on royalty, and I fail to see any special

indication

pointing to the early third century, as De Blois does. Two

very similar

pieces

of advice from the fourth century B.C. can be found in Isocrates and

Aristotle.

Isocrates (Ep.

7.4) preaches to Timotheus of Heraclea the usual respect for the

possessions

of the rich, while Aristotle (Politica 5

1310b40-1311a2) states that the

king ensures that neither

the

wealthy nor the mass of the people suffer injustice - a

clear

parallel with the policy of running with the hare and hunting with the

hounds

advised by Philostratus' Apollonius.

There are,

admittedly, passages in the Life

of

Apollonius that can be interpreted as an allusion to Roman

military

policy.

For example, in book 2 chapter 26, the Indian king Phraotes

tells

Apollonius that he keeps the barbarians on his borders in check by

payments,

and even uses them as border troops. This policy, which is judged very

positively by Apollonius, must have been interpreted by at least a

significant

part of Philostratus' readers as alluding to a Roman practice that was

common

in the early third century. This has been pointed out by Herbert Grassl, and

Schtajerman took this passage to reflect Philostratus' own point of

view: the

Athenian sophist was, in her opinion, advocating a low-profile military

policy.

It is not improbable that Philostratus was aware of some of the

problems

connected with the defence of the borders of the empire; after all, he

had been

present in the imperial headquarters during Caracalla's operations on

the Rhine and Danube border in 213. But are we

entitled to understand Phraotes' policy and Apollonius' approval as

reflecting Philostratus' own opinion?

For the moment, I will leave this question unanswered

and turn to a third objection to political interpretations of the

Life of

Apollonius. The description of the activities and

utterances of the

main

character in the realm of politics is an important component of

Philostratus'

portrayal of Apollonius as a philosopher rather than as an obscure

miracle

worker. In other words, Apollonius' alleged contacts with emperors and

his

interventions in civic life in Greek cities are essential to

Philostratus'

professed apologetic programme. The

early imperial age had an

aggregate of

clear-cut conceptions of the socio-political role of the

philosopher. These

conceptions, which had their roots in the Classical and

early-Hellenistic

periods, have been listed and analysed by Johannes

Hahn in Der

Philosoph und

die Gesellschaft. Philostratus modelled his hero in

accordance with

these conceptions. In his contacts with Vespasian and Titus,

Philostratus'

Apollonius is the philosophical adviser of the virtuous king; the

confrontation with Domitian is presented as the crowning event of a

tradition

of philosophical resistance to despotism, and Apollonius reveals

himself as an

undaunted adversary of a tyrant. By intervening in situations of civic

discord, Philostratus' hero fulfils another expectation bound up

with the

philosopher's role: the philosopher as an impartial arbiter of

conflicts.

Political interpretations of the

Life of Apollonius tend to assume

that the employment of such conceptions by Philostratus in his

portrayal of

Apollonius betrays the sophist's own convictions. Schtajerman, for

example,

concluded from the behaviour towards Domitian attributed to Apollonius

that

the author of the Life,

despite his predilection for strong imperial

authority, was opposed to tyrannical regimes. I am afraid that this

amounts to

an unacceptable identification of the author with the main character of

his

work. If Philostratus wanted to portray Apollonius as a philosopher, he

had to

turn to deeply rooted and widely held conceptions of the philosopher's

role,

such as the philosopher as the opponent of a tyrant. We should not

forget that

such conceptions were rather idealistic. I venture the suggestion that

many

philosophers were wise enough not to model their actual behaviour in

relations

with autocrats on such conceptions. The claim that a sophist shared

these conceptions

cannot be considered valid on the basis of their presence in a literary

text

such as the Life of

Apollonius. To make such a claim acceptable, one

should adduce evidence from Philostratus' other writings.

This brings me to my fourth objection to political

interpretations of the Life

of Apollonius: only too often, scholars

who

have proposed such interpretations have neglected, insufficiently

digested or

misinterpreted Philostratus' other writings, especially the Lives of

the

sophists. Among Philostratus' writings, this work, in

which he deals

with

his own cultural milieu and that of his predecessors, should take pride

of

place as a source for the Athenian sophist's values and convictions.

The views

on the relations between Greek intellectuals and Roman emperors that he

expresses in the biographies of his cultural heroes are markedly

different from

the idealised conceptions of the relations between philosophers and

rulers

that we find in the Life

of Apollonius. There is, of course, a certain

amount of common ground.  Both

in the Life of

Apollonius

and in the

Lives

of the sophists, emperors are expected to show respect

towards people

who

represent Greek culture. This does not mean, however, that the

relations

between monarchs and Greek intellectuals as envisaged in the Lives of

the

sophists exhibit the idealised conceptions that we find

embodied in

the Life

of Apollonius. Philosophers were expected to

display

frankness in

voicing

criticism of monarchs: the ideal of parrhēsia.

Philostratus' advice,

on

the other hand, is “not to provoke tyrants or excite to wrath their

savage

dispositions” (Vitae

sophistarum 500), and he condemns the behaviour of his

senior

colleague

Antipater, who openly lamented the murder of Geta by Caracalla, as

essentially

foolish (Vitae

sophistarum

607). Philosophers were expected to cast themselves in the

role of

moral and spiritual guide and personal confidant in their relations

with those

in power. Philostratus, on the other hand, views the relations between

emperors and Greek intellectuals - philosophers and sophists alike -

almost exclusively in terms of cultural patronage. For example,

Hadrian's

interest in Greek culture was, according to Philostratus, a form of

diversion

from imperial concerns (Vitae

sophistarum 490). He certainly does not disdain such a

view of

Greek literary culture; on the contrary, in the preface to the Lives

of the

sophists he expresses the hope that his work will serve

precisely this

entertainment function for Gordian (Vitae

sophistarum 480).

Both

in the Life of

Apollonius

and in the

Lives

of the sophists, emperors are expected to show respect

towards people

who

represent Greek culture. This does not mean, however, that the

relations

between monarchs and Greek intellectuals as envisaged in the Lives of

the

sophists exhibit the idealised conceptions that we find

embodied in

the Life

of Apollonius. Philosophers were expected to

display

frankness in

voicing

criticism of monarchs: the ideal of parrhēsia.

Philostratus' advice,

on

the other hand, is “not to provoke tyrants or excite to wrath their

savage

dispositions” (Vitae

sophistarum 500), and he condemns the behaviour of his

senior

colleague

Antipater, who openly lamented the murder of Geta by Caracalla, as

essentially

foolish (Vitae

sophistarum

607). Philosophers were expected to cast themselves in the

role of

moral and spiritual guide and personal confidant in their relations

with those

in power. Philostratus, on the other hand, views the relations between

emperors and Greek intellectuals - philosophers and sophists alike -

almost exclusively in terms of cultural patronage. For example,

Hadrian's

interest in Greek culture was, according to Philostratus, a form of

diversion

from imperial concerns (Vitae

sophistarum 490). He certainly does not disdain such a

view of

Greek literary culture; on the contrary, in the preface to the Lives

of the

sophists he expresses the hope that his work will serve

precisely this

entertainment function for Gordian (Vitae

sophistarum 480).

Here we

touch on the

wider issue of the conceptions that sophists themselves held of the

social

function of their chosen profession. Obviously, this is too

comprehensive a

problem to be dealt with in brief, even if I had a firm view of the

matter -

which I have not. I can only say that I am inclined to side with those

scholars

who stress the self-awareness of the sophists as artists and who tend

to play

down their alleged sense of public responsibility. Aelius Aristides,

in one of

the most moving passages from his

To Plato: in defence of oratory,

compares his dedication to oratory with an addiction to alcohol or sex

(or.

2.432 Behr). The point of this comparison is, as Aristides himself

makes

explicit, the

personal and unsocial character of his enjoyment of practicing

eloquence. He

adds, however, that he derives from oratory "a joy and pleasure perhaps

more

fitting of a free man." This passage sums it up beautifully. There is

no

pretence of a function of oratory in political life; a few lines

earlier,

Aristides has explicitly stated that, due to changes in political

reality, such

pretensions are outmoded. Oratory is a goal in itself. On the other

hand, it

has a social function in that it is a mark of distinction of the

gentleman. It

is an asset valued both for its own sake and as a strategy of social

distinction.

The person who masters the intricacies of sophistic eloquence

accumulates symbolic

capital - to use a fashionable but not wholly inappropriate

Parisian expression.

The objections to political interpretations of the Life

of Apollonius that I have listed can be subsumed under two

headings. On

the

one hand, such interpretations tend to assume that the author's

opinions and

convictions can be deduced from the repertoire that he employs in

portraying

his protagonist as a philosopher involved in politics: a repertoire

consisting

of historical details, standard ingredients from speeches on kingship

and

conventional conceptions of the philosopher's role. In the second

place, such

interpretations tend to disregard the evidence for Philostratus'

outlook

contained in the Lives

of the sophists.

Allusions

to the

Severan period in the Life

of Apollonius

The objections to

interpretations of the Life

of Apollonius as Tendenzliteratur

that I have put forward so far do not imply that the possibility can be

ruled

out that the Life

contains incidental allusions to early third century

situations and events. In fact, I have left open the possibility of

reading

allusions to the murder of Geta in Philostratus' version of the death

of Titus (VA

6.32) and to Roman payments to barbarian enemies in

the policy

ascribed to

the Indian king Phraotes (VA

2.26). Before dealing with these and

similar

cases, however, I shall try to formulate some criteria that should be

followed

in attempting to track down allusions.

I think that there are two types of case in which it is

justified to suspect allusions to early third-century events and

situations:

when in describing first-century actions or situations and the comments

on them

by the protagonist of the Life

of Apollonius, the author commits

certain

evident anachronisms which reflect recent events or the situation of

his own

day; and when there are very close correspondences between activities

attributed to first-century emperors and rulers outside the Greco-Roman

world

in the Life,

on the one hand, and the actions of early third-century

emperors, on the other. In both cases, it must be shown to be plausible

that

contemporaries of Philostratus who were reasonably well informed about

the

relations in court and the course of action of the imperial

administration in

the previous decades must have been reminded of recent events or

existing

situations when they read certain passages in the Life. Only in cases

where these criteria are satisfied can we speak of a genuine allusion.

What results do

we get when we apply such criteria? I

think that it is almost inevitable to conclude that the report of

Titus' death

and the alleged part of Domitian in it must have been understood by

Philostratus' readers as an allusion to the murder of Geta by

Caracalla, and

the same applies to the report of Phraotes' habit of buying off

barbarian

invasions: readers of

the Life

must have understood the passage as

alluding to Roman practice. In 'The pepaideumenos in action', Graham

Anderson has made the interesting suggestion that the claim

of a

foolish

Indian king that he is 'identical with the Sun' is an allusion to

Elagabalus

(VA 3.28).

I think that Anderson is right, and I would take this as a

confirmation of Göttsching's dating

of the completion of the Life

of Apollonius after Elagabalus' death in

222. In drawing conclusions from allusions such as these, however,

great

caution should be exercised. To take one example, I do not want to deny

that

Philostratus regarded imperial fratricide as a regrettable form of

action and

that he probably retained rather unpleasant memories of his stay in the

Severan

court as far as the years 211 and 212 were concerned. This seems to be

confirmed by his letter to an ‘Antoninus', possibly Caracalla, accusing

the

addressee of having sacked his own house (Ep. 72), a letter

which, I suspect, was written after 217. In view of Philostratus'

reaction to

the behaviour of his colleague Antipater in connection with the murder

of Geta,

however, it seems likely that his main conviction in matters of this

kind was

that they were no concern of his.

readers of

the Life

must have understood the passage as

alluding to Roman practice. In 'The pepaideumenos in action', Graham

Anderson has made the interesting suggestion that the claim

of a

foolish

Indian king that he is 'identical with the Sun' is an allusion to

Elagabalus

(VA 3.28).

I think that Anderson is right, and I would take this as a

confirmation of Göttsching's dating

of the completion of the Life

of Apollonius after Elagabalus' death in

222. In drawing conclusions from allusions such as these, however,

great

caution should be exercised. To take one example, I do not want to deny

that

Philostratus regarded imperial fratricide as a regrettable form of

action and

that he probably retained rather unpleasant memories of his stay in the

Severan

court as far as the years 211 and 212 were concerned. This seems to be

confirmed by his letter to an ‘Antoninus', possibly Caracalla, accusing

the

addressee of having sacked his own house (Ep. 72), a letter

which, I suspect, was written after 217. In view of Philostratus'

reaction to

the behaviour of his colleague Antipater in connection with the murder

of Geta,

however, it seems likely that his main conviction in matters of this

kind was

that they were no concern of his.

Two other passages which meet my criteria for being taken

as allusions to early third-century situations deserve more serious

consideration as evidence of Philostratus' concerns. The first of

these (VA

7.42) is a charming story about a boy from Messene whom

Apollonius meets in Domitian's dungeons. The reason for the boy's

captivity is

his refusal to give in to the emperor's amorous advances, but he blames

his

father in the first place for his unenviable situation. Instead of

giving him a

proper Greek education, his old man has sent him to Rome to study law.

Fortunately, the boy has at least fruitfully followed the lessons of a

grammaticus, so he has a ready answer to Apollonius' allusion to

Hippolytus.

The anecdote is clearly anachronistic; it reflects the situation in

the second

half of the second and early third centuries, when the study of Roman

law

became popular among young men from the eastern provinces. The

development is

beautifully illustrated by the autobiography of Gregory the

Wonder-worker, who

in the 230s was told by his tutor that the study of Roman law opened up

several

attractive career perspectives. It is a development that must have

filled a

sophist such as Philostratus with apprehension; for the author of the

Lives

of the sophists literary culture was the quintessence of a

cherished

Greek

identity. In spite of the playful character of the allusion, something

of this

apprehension shows through in the anecdote about the boy from Messene.

The

second allusion that may be evidence of Philostratus'

concerns is Apollonius' final recommendation to Vespasian (5.36) .

The sage

advises the emperor to send Greek-speaking proconsuls to Greek public

provinces, while Latin-speaking public provinces should be ruled by

Latin-speaking proconsuls. The motivation of this advice is a sign of a

relatively far-reaching identification with the exercise of Roman rule:

Apollonius refers to the case of a proconsul of Achaea who was

insufficiently familiar

with Greek customs and became a plaything of his provincial assessores.

The advice itself, however, expresses an equally far-reaching desire

that the

emperor should take Greek identity into account in selecting governors

for the

eastern provinces. The fact is that the contrast of 'Greek-speaking'

and 'Latin-speaking'

candidates for governorships probably means that 'Greek-speaking'

candidates

are not just people with a working knowledge of Greek. After all, an

overwhelming

majority of senators from Italy and

the west must have been reasonably fluent in that language. It is, I

think,

almost unavoidable to conclude that Philostratus' hero advises the

emperor to

select people from the eastern half of the empire, whose mother tongue

was

Greek, as governors of eastern provinces. In relation to the dramatic

date of

Apollonius' speech, the year 69, this piece of advice seems to be

anachronistic: although there was to be a notable increase in the

number of

senators of eastern origin under the Flavian dynasty, and although

several of

them were promoted to governorships in the eastern provinces, I prefer

to think

that Apollonius' recommendation reflects the situation in the Antonine

and

Severan periods, when a significant part of the senatorial order was of

eastern

origin. According to Geza Alföldy,

the evidence for the period 138 -

160 shows

a clear trend for senators from the Greek east to be appointed as

imperial

legates in eastern rather than in western provinces, and the same

tendency can

be detected in the holding of praetorian and consular proconsulates. In

his

continuation of Alföldy's work for the period 180-235, Paul Leunissen

claims

that the available evidence suggests a break in this trend: in

appointments of

imperial legates, no tendency to take the geographical provenance of

the

candidates into account can be detected. As far as proconsulates are

concerned, substantial evidence is only available for the proconsulate

of Asia, but this is rather striking: of

the 21 proconsuls whose geographical provenance is known, twelve

certainly came

from the western half of the empire, and another six probably came from

there

as well. I have to admit that I always become slightly nervous when I

see the

prosopographical evidence on which such claims are based. If, however,

Leunissen is right, it seems plausible that this development was to a

certain

extent perceived by the social elite in the Greek-speaking provinces,

and this

may have resulted in a measure of dissatisfaction. I find it very

attractive

to suppose that the advice which Philostratus puts into the mouth of

his hero

and for which, of course, no precedent at all existed in speeches on

kingship,

is an expression of this dissatisfaction.

If this proposal is acceptable, this would mean that,

although literary culture was essential to Philostratus' conception of

Greek

identity, his highly pronounced Greek self-awareness also found

expression in

an interest in the manning of the governorships of the eastern

provinces. This

is not really surprising: even though the importance of careers in the

imperial administration in providing status is sometimes played down in

the Lives

of the sophists in favour of sophistic achievements, an

interest in

such

careers is evident from almost every page of this work. Just like the

story

about the boy from Messene, Apollonius' advice on the manning of

proconsular posts alludes to the

kind of issues that did concern Philostratus: the cultural identity and

prestige of the social elite in the eastern half of the empire.

Concluding remarks

In sum, I think that

interpretations of the Life

of Apollonius as a politically tendentious

piece of writing mistake the author's repertoire for his convictions

and values

and often amount to neglect of the more direct evidence for

Philostratus' outlook contained in the Lives

of the sophists. On the other hand, I

hope to have succeeded in demonstrating that a plausible case can be

made for

the existence of incidental allusions to early third-century events and

situations in the Life

of Apollonius. The number of such cases could

probably be increased. We should not presume, however, that such

allusions

testify to Philostratus' concerns and opinions on current affairs

unless

additional evidence from his other writings can be adduced. Such

evidence

suggests that special significance should be attributed to the

allusions to the

appeal that the study of Roman law held for Greeks, and to the

appointment of

governors in the Greek provinces of the empire. They bear witness to

Philostratus' preoccupations and interests, while other allusions are

evidence

of a rather unsystematic perception of some aspects of contemporary

reality.

With due respect for Alföldy and De Blois, I think that signs of a

consciousness of an impending or actual crisis are hard to find in

Philostratus'

writings. The Lives of

the sophists lack any of Cassius Dio's nostalgia

for the Antonine period. Perhaps the value of Philostratus' writings as

a

source for the attitudes to be found among the social elite in the

eastern half

of the empire in the Severan period should be looked for as much in the

limitations to his perception as in what he did perceive.

Titles

mentioned

Alföldy,

G.

(1974), 'The crisis of the third century as seen by

contemporaries', GRBS 15: 89-111 [reprinted in: Die

Krise des

römischen Reiches. Geschichte, Geschichtsschreibung, und

Geschichtsbetrachtung. Ausgewählte Beiträge (Stuttgart 1989),

319-341].

Back to text.

Alföldy,

G.

(1977), Konsulat und Senatorenstand unter den

Antoninen. Prosopographische Untersuchungen zur senatorischen

Führungsschicht

(Bonn).

Back

to text.

Anderson,

G.

(1986), Philostratus. Biography and belles lettres

in the third century AD (London).

Back to text.

Anderson,

G.

(1989), 'The pepaideumenos in action: sophists

and their outlook in the Early Empire', in: ANRW

2.33.1: 79-208.

Back to text.

Blois,

L. de

(1984), 'The third century crisis and the Greek elite

in the Roman empire', Historia 33: 258-277.

Back to text.

Bowie,

E.L.

(1978), 'Apollonius of Tyana: tradition and reality',

in: ANRW 2.16.2: 1652-1699.

Back to text.

Calderini,

A.

(1940/1), 'Teoria e pratica politica nella "Vita di

Apollonio di Tiana"', RIL 74: 213-241.

Back

to text.

Gabba,

E.

(1955), 'Sulla Storia Romana di Cassio Dione',

RSI 67: 289-233.

Back to text.

Göttsching,

J. (1889),

Apollonius von Tyana (Leipzig)

[dissertation].

Back to text.

Grassl,

H.

(1982), Sozialökonomische Vorstellungen in der

kaiserzeitlichen griechischen Literatur (1.-3 Jh. n.Chr.)

(Wiesbaden).

Back to text.

Hahn,

J.

(1989), Der Philosoph und die Gesellschaft.

Selbstverständnis,

öffentliches Auftreten und populäre Erwartungen in der hohen Kaiserzeit

(Stuttgart).

Back to text.

Lenz,

F.W.

(1964), 'Die Selbstverteidigung eines politischen

angeklagten. Untersuchungen zu der Rede des Apollonios von Tyana bei

Philostratos', Das Altertum 10: 95-110.

Back to text.

Leunissen,

P.M.M.

(1989), Konsuln und Konsulare in der Zeit von

Commodus bis Severus Alexander (180-235 n.Chr.). Prosopographische

Untersuchungen zur senatorischen Elite im römischen Kaiserreich

(Amsterdam).

Back to text.

Miller,

J.

(1890), review of Göttsching (1889), Berliner

Philologische Wochenschrift 10: 1422-1426.

Back to text.

Palm,

J.

(1976), Om Philostratos och hans Apollonios-biografi

(Uppsala).

Back to text.

Schtajerman,

E.M.

(1964), Die Krise der Sklavenhalterordnung im

Westen des römischen Reiches (Berlin).

Back

to text.

Solmsen,

F. (1941), 'Philostratos

(9)-(12)', in: RE

20.1: 124-177 [= Kleine

Schriften 2 (1968),

92-118].

Back to text.

Philostratus was a member of a family

which

belonged to the upper echelons of the Athenian citizen body and which

produced

members of the senatorial order in the next generation. He was

probably a

member of the Athenian council and held the position of hoplite general

in that

city in the first decade of the third century. Moreover, for some ten

years he

was a protégé of Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus and the

mother of

his successor Caracalla. The

Life of Apollonius itself was

commissioned by the empress, although it was completed after her death

in 217.

Philostratus' other major work, the Lives of the sophists,

was dedicated

to the proconsul of Africa, Gordian senior, in the winter of

237/238. As for the contents of

the Life of Apollonius,

even a cursory reading is sufficient to convey

the impression that the protagonist is a philosopher involved in

politics, a

man who intervenes in civic conflicts and who establishes relations of

varying

cordiality with several first-century emperors, among them Vespasian,

Titus and

Domitian. Besides, even students familiar with imperial Greek

literature will

be struck by the presence of a very pronounced sense of Greek

superiority in

the Life.

At first sight, therefore, the search for a political tenor

in the Life of

Apollonius

does not seem too far-fetched.

Philostratus was a member of a family

which

belonged to the upper echelons of the Athenian citizen body and which

produced

members of the senatorial order in the next generation. He was

probably a

member of the Athenian council and held the position of hoplite general

in that

city in the first decade of the third century. Moreover, for some ten

years he

was a protégé of Julia Domna, the wife of Septimius Severus and the

mother of

his successor Caracalla. The

Life of Apollonius itself was

commissioned by the empress, although it was completed after her death

in 217.

Philostratus' other major work, the Lives of the sophists,

was dedicated

to the proconsul of Africa, Gordian senior, in the winter of

237/238. As for the contents of

the Life of Apollonius,

even a cursory reading is sufficient to convey

the impression that the protagonist is a philosopher involved in

politics, a

man who intervenes in civic conflicts and who establishes relations of

varying

cordiality with several first-century emperors, among them Vespasian,

Titus and

Domitian. Besides, even students familiar with imperial Greek

literature will

be struck by the presence of a very pronounced sense of Greek

superiority in

the Life.

At first sight, therefore, the search for a political tenor

in the Life of

Apollonius

does not seem too far-fetched. ,

certainly falls within the limits of political

interpretations

in the proper sense of the word. Göttsching claimed that with the

establishment

of the Severan dynasty the imperial power had passed into the hands of

African

and Asiatic barbarians. In reaction to this development, which was

lamented

by traditionally-minded Romans and cultured Greeks alike, Philostratus

assigned his hero the role of 'Herold des Hellenismus', 'herald of

Hellenism'. According to Göttsching, the stark contrast

between

Hellenic

virtues and barbarian vices that is to be found in the Life should be

read in this light. Göttsching also claimed to be able to detect

numerous

allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors. Thus he believed

that the

descriptions of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian and their mutual

relations

presented Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla in disguise, while

Philostratus'

portrait of Nero stood for that of Elagabalus. Assuming that the

writer would

not have dared to publish a work of this kind during the reign of

Elagabalus,

so that the Life

could not have been issued before the reign of Severus

Alexander, Göttsching formulated the hypothesis that at least one of

Philostratus' intentions was to advise the young emperor by means of

the

explicit recommendations and the positive and negative examples of

monarchical

behaviour contained in the

Life of Apollonius.

,

certainly falls within the limits of political

interpretations

in the proper sense of the word. Göttsching claimed that with the

establishment

of the Severan dynasty the imperial power had passed into the hands of

African

and Asiatic barbarians. In reaction to this development, which was

lamented

by traditionally-minded Romans and cultured Greeks alike, Philostratus

assigned his hero the role of 'Herold des Hellenismus', 'herald of

Hellenism'. According to Göttsching, the stark contrast

between

Hellenic

virtues and barbarian vices that is to be found in the Life should be

read in this light. Göttsching also claimed to be able to detect

numerous

allusions to the behaviour of the Severan emperors. Thus he believed

that the

descriptions of Vespasian, Titus and Domitian and their mutual

relations

presented Septimius Severus, Geta and Caracalla in disguise, while

Philostratus'

portrait of Nero stood for that of Elagabalus. Assuming that the

writer would

not have dared to publish a work of this kind during the reign of

Elagabalus,

so that the Life

could not have been issued before the reign of Severus

Alexander, Göttsching formulated the hypothesis that at least one of

Philostratus' intentions was to advise the young emperor by means of

the

explicit recommendations and the positive and negative examples of

monarchical

behaviour contained in the

Life of Apollonius. As

a result of the decline of the cities,

this

intelligentsia became increasingly dependent on the provincial

aristocracy, a

dependency which was accompanied by feelings of hostility on the part

of

clients towards their patrons. The imperial bureaucracy offered a way

out of this

dependency. However, Caracalla objected to sophists and other

representatives

of the intelligentsia. At the instigation of Julia Domna, who

disagreed with

her son on this score, Philostratus addressed his Life of Apollonius

to

the municipal aristocracy with a political programme that reflected the

interests and views of this aristocracy. His political ideal was an

empire, as

it had been in the Antonine period, founded on a smoothly functioning

urban

self-government. This ideal implied respect for the rights of the

social elite

in the cities; at the same time, it demanded that the members of this

elite

should not evade their obligations and should allow the rest of the

citizen

body to share to some extent in their possessions in order to

guarantee social

harmony. The implementation of this ideal was to be guaranteed by a

strong

imperial authority, which must neither degenerate into tyranny, nor be

dependent on the representative body of the provincial aristocracy,

the

senate. As regards foreign policy, the municipal aristocracy, unlike

the

provincial aristocracy, advocated a policy of peace: plans of conquest

should

be abandoned and war should be avoided at all costs.

As

a result of the decline of the cities,

this

intelligentsia became increasingly dependent on the provincial

aristocracy, a

dependency which was accompanied by feelings of hostility on the part

of

clients towards their patrons. The imperial bureaucracy offered a way

out of this

dependency. However, Caracalla objected to sophists and other

representatives

of the intelligentsia. At the instigation of Julia Domna, who

disagreed with

her son on this score, Philostratus addressed his Life of Apollonius

to

the municipal aristocracy with a political programme that reflected the

interests and views of this aristocracy. His political ideal was an

empire, as

it had been in the Antonine period, founded on a smoothly functioning

urban

self-government. This ideal implied respect for the rights of the

social elite

in the cities; at the same time, it demanded that the members of this

elite

should not evade their obligations and should allow the rest of the

citizen

body to share to some extent in their possessions in order to

guarantee social

harmony. The implementation of this ideal was to be guaranteed by a

strong

imperial authority, which must neither degenerate into tyranny, nor be

dependent on the representative body of the provincial aristocracy,

the

senate. As regards foreign policy, the municipal aristocracy, unlike

the

provincial aristocracy, advocated a policy of peace: plans of conquest

should

be abandoned and war should be avoided at all costs. I

should add that this holds true regardless of the question as to

whether he

found some indications for contacts of Apollonius with emperors in

traditions

directly connected with the Tyanean sage. Even where Philostratus had

access

to such traditions, he elaborated them with material taken from

imperial

biographical and historiographical sources. The results of his efforts

are

quite respectable, in spite of some chronological mistakes and

historical

improbabilities.

I

should add that this holds true regardless of the question as to

whether he

found some indications for contacts of Apollonius with emperors in

traditions

directly connected with the Tyanean sage. Even where Philostratus had

access

to such traditions, he elaborated them with material taken from

imperial

biographical and historiographical sources. The results of his efforts

are

quite respectable, in spite of some chronological mistakes and

historical

improbabilities. ,

refer to earlier

instances of

emperors having eliminated their brothers, explicitly citing the case

of

Domitian and Titus. However, by reckoning with the

probability that

Philostratus did a quite respectable amount of homework for his

portraits of