In

de wintermaanden van

2014-2015 boog de

opleidingscommissie van Archeologie, Griekse en Latijnse Taal- en

Cultuur en Oudheidkunde aan de Vrije Universiteit zich meerdere malen

over een klacht van een studente Religiewetenschappen, die korte tijd

de minor Antieke Cultuur had gevolgd. Haar onvrede gold vooral het

onderwijs in

de Oude Geschiedenis. Dit onderwijs, vond

zij, droeg bij tot 'een eurocentrische en racistische kijk op de

geschiedenis, waarin de zwarte mens miskend wordt in zijn (enorme!)

bijdrage aan westerse civilisatie.' De opleidingscommissie wees haar

klacht van de hand. Je kunt de mailwisseling

hier

nalezen. Voor de klaagster was de kous daarmee niet af, en op haar

initiatief vond in juni 2015 een openbaar debat plaats tussen

enerzijds twee leden van de opleidingscommissie,

Gerard

Boter en

Jaap-Jan Flinterman (webmaster van deze site en destijds docent Oude

Geschiedenis), en anderzijds Sandew Hira en

Djehuti-Ankh-Kheru, die met de klaagster van mening waren dat bij

Oudheidkunde

aan de VU geen wetenschappelijk onderwijs wordt gegeven, maar 'de

ideologie van de witte suprematie' wordt verkondigd.

Een volledige

weergave van het debat kun je op

You Tube bekijken. Met dat debat

was de botsing van meningen overigens nog niet afgelopen. In november

2015 kwam

Advalvas,

het universiteitsblad van de VU, met een

nabeschouwing. Sandew Hira en

Djehuti-Ankh-Kheru waren niet tevreden over het artikel, en kwamen op

hun eigen website op de zaak

terug. In juni 2016 kruisten we wéér de degens, in de rubriek

'Contramine' van het

Tijdschrift

voor Geschiedenis 129.2, 241-250. Onze bijdrage kun je

hier

lezen. En

in juni 2017 plaatste

Lampas,

het tijdschrift voor Nederlandse classici, twee artikelen van

mijn

hand over de mythe dat de Grieken zich tijdens de

verovering van

Egypte door Alexander de Grote daadwerkelijk Egyptische wijsheid zouden

hebben toegeëigend door een Egyptische bibliotheek te plunderen:

'

Gestolen erfenis 1: diefstal in Alexandrië'

en '

Gestolen erfenis 2:

tempelroof in Rakote'. In oktober van datzelfde jaar

publiceerde Djehuti-Ankh-Kheru in eigen beheer een boek met

de fraaie titel

Boterzacht

en Flinterdun. De Ontmaskering van Eurocentrisme

(Amsterdam: The Grapevine Publications, 2017). Een

appendix in dat boek (blz. 183-200: 'Het Alexandriësyndroom') was

gewijd aan een kritische bespreking van mijn

Lampas-artikelen.

In deze tekst uit de zomer van 2019 (

Gestolen erfenis 3: Alexandria revisited)

houd ik zijn argumenten tegen het licht.

Wat

mankeerde er volgens de klaagster en haar achterban aan het

onderwijs in de Oude Geschiedenis op de VU? Welnu, de docent Oude

Geschiedenis wiens onderwijs zij zou volgen,

vertelt zijn studenten niet dat de Griekse cultuur uit Zwart Afrika

komt. Hij vindt dat geen serieuze bijdrage aan de wetenschappelijke

beeldvorming

van de geschiedenis van de Oudheid, en de opleidingscommissie was dat

met hem eens.

Dat

de wortels van de Griekse beschaving in Zwart Afrika liggen, is het

centrale leerstuk van wat

doorgaans als afrocentrisme

wordt aangeduid. De mailwisseling en de voorbereiding op het

debat

hebben me veel geleerd over deze stroming, en ik heb gemerkt dat ook

bij anderen

die met afrocentrisch gedachtegoed worden geconfronteerd, behoefte

bestaat aan goede informatie. De webpagina waarnaar je hierboven een

link aantreft, is een poging in die behoefte te voorzien. Hij bevat

(naast een heel korte typering van het afrocentrische gedachtegoed)

links naar websites waarop kritisch, maar serieus wordt

ingegaan op afrocentrische opvattingen, en er is ook een lijstje met

een paar boeken over deze stroming opgenomen.

Voor

Lampas 56.1 (2023) schreven

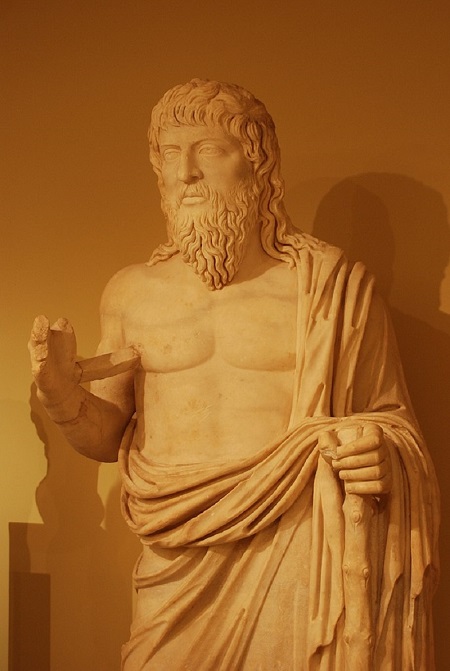

Mieke Prent en ik een artikel over het Asklepieion in de oud-Griekse stad

Messene. Messene was de centrale stadstaat van Messenia, het zuidwestelijke

deel van de Peloponnesos. Sinds de archaïsche periode van de Griekse

geschiedenis was dat landschap in handen geweest van Sparta, maar in 369

v.Chr. dwong de Thebaanse veldheer Epameinondas de Spartanen het grootste deel

van Messenia op te geven en legde hij de fundamenten voor een nieuwe stad.

In het

artikel in Lampas ligt

het accent op het heiligdom dat

in de eerste helft van de tweede eeuw v.Chr. in het centrum van Messene

werd gebouwd voor de genezende god Asklepios – over de resten van

een ouder heiligdom

heen. Het artikel moest ook een korte schets van de geschiedenis van

Messenia

bevatten, gedurende de periode van de stichting van de stad in 369 tot

de vestiging

van de Romeinse hegemonie over Griekenland rond het midden van de

tweede eeuw

v.Chr. Ik schreef daarvoor een voorstudie. Voor het artikel in

Lampas was

die veel te lang, maar mensen die zich willen verdiepen in de Messeense

geschiedenis – of meer in het algemeen in de geschiedenis van de

Peloponnesos in de hellenistische periode – vinden

het stuk misschien wel handig.

Ik hoop dat vooral universitair werkzame

oudhistorici die college willen geven over de hellenistische Peloponnesos, er hun voordeel mee kunnen doen. Dat is het

kader waarin ik mijzelf met de materie vertrouwd heb gemaakt: in de jaren 2016

tot 2019 verzorgden Mieke Prent en ik aan de Vrije Universiteit een

archeologisch-historisch werkcollege over de hellenistische Peloponnesos voor

gevorderde bachelor-studenten Oudheidkunde/Oudheidstudies, (Oude) Geschiedenis

en (Mediterrane) Archeologie. Ook bij de voorbereiding van excursies zou de webpagina misschien van pas kunnen komen.

Het stuk achter bovenstaande link geeft een vrij

compleet overzicht van wat we van de politieke geschiedenis van Messene in de

hellenistische periode weten en, omdat de annotatie nogal ruim bemeten is,

krijgt de lezer ook een beeld van het bronnenmateriaal waarop onze kennis van

die geschiedenis is gebaseerd. Helemaal aan het slot van de webpagina, na de noten

en bibliografie, geef ik een overzicht van de bronnen en signaleer ik

de voornaamste wetenschappelijke literatuur. Voor vragen, opmerkingen,

kanttekeningen, aanvullingen en correcties houd ik mij aanbevolen.

This is the

complete translation of a short French-language note published in the

Zeitschrift

für Papyrologie

und

Epigraphik

70, 1987, 171-172:

'Sur les lignes 11-13 de l'inscription de

Laodice'. It

adduces a parallel for a

phrase from the so-called Laodice inscription: an epigraphic

dossier

concerning the sale, by the

Seleucid

king Antiochus II to his wife or former wife Laodice, of the village of

Pannucome.

The sale

can

be

dated to the year 253 BC; Pannucome was situated in what is now

northwestern Turkey, near the modern city of Gönen. In the 1970's and

1980's

there was some

discussion about the question whether the peasants from the

village were included in the sale. I

thought

(and still think) that they were, and that the parallel adduced in this

note

proves that this is the correct interpretation of the royal letter that

constitutes the central document of the dossier.

Unfortunately, the

misunderstanding I tried to dispel in my 1987 contribution still crops

up

in

items of the standard bibliography on the position of native peasants

in Asia Minor.

That is why in 2012, after a quarter of a century, I returned

to the subject: 'Pannucome

revisited: lines

11-13 of the Laodice inscription again',

ZPE 181, 2012,

79-87.

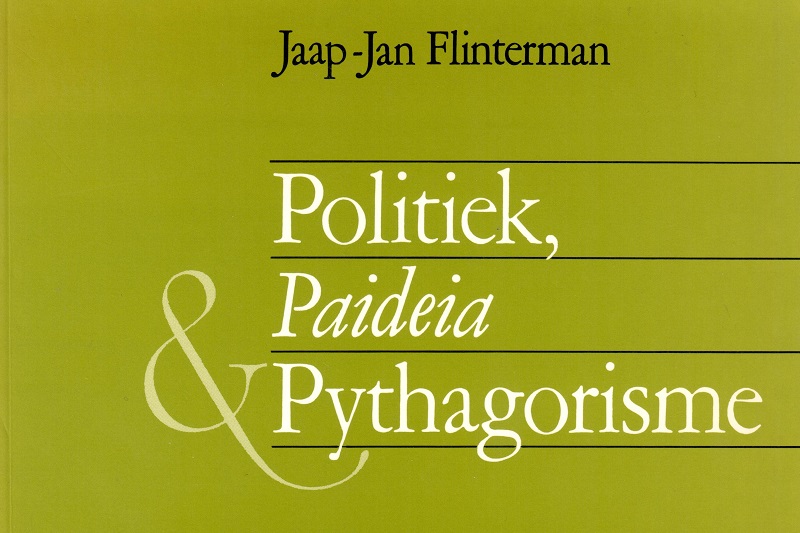

The Dutch language

version of

Power,

Paideia

&

Pythagoreanism. Greek

Identity, Conceptions of the Relationship

between Philosophers and Monarchs, and Political Ideas in Philostratus'

Life of

Apollonius (Amsterdam,

Gieben: 1995)

was published in 1993 by Styx Publications in

Groningen;

it was my doctoral dissertation (

full text), supervised by Lukas de

Blois, Professor of Ancient History at the University of

Nijmegen. In

the Netherlands,

dissertations

written in Dutch have to contain a summary in a language

accessible to an international readership. Since at the time I did not

know whether I would receive a translation grant, I wrote a

fifteen-page summary in English (pp. 307-321). The publication, in

1995, of the

translation by Peter Mason made the summary redundant as a device to

bring my dissertation

to the attention of an international readership. However,

it may still

come

in handy for those who think a 240-page monograph on the

Life of

Apollonius

a bit

too much of a good thing; and it may also be

helpful to

people who

want to complement a partial reading of the book by perusal of a

synopsis. Therefore, I have decided to put it online, even though I

must ask the

reader for his or her clemency, because it was my first extended

exercise in English prose composition. Superfluous to say that

things such as references and bibliography are almost completely

missing. For those see

the

book. The summary of the

Dutch-language version is preceded by the table of contents of the

English version.

Presenting an up-to-date bibliography on

the

Life of

Apollonius

would be quite time-consuming. Two volumes

of papers, on the

Life

of

Apollonius

and on Philostratus respectively, were published in 2009: Kristoffel

Demoen, Danny Praet (eds),

ΘΕΙΟΣ ΣΟΦΙΣΤΗΣ.

Essays on Flavius Philostratus’ Vita Apollonii (Leiden:

Brill

2009); Ewen Bowie, Jas

Elsner

(eds),

Philostratus

(Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press

2009). My contribution to the former volume can be found

here.

One of the editors of

ΘΕΙΟΣ ΣΟΦΙΣΤΗΣ,

Kristoffel Demoen, also

supervised a fascinating dissertation on the

Life of Apollonius:

Wannes

Gyselinck,

Talis

oratio, qualis vita. Een tekstpragmatisch onderzoek naar de poëtica van

Flavius Philostratus' Vita Apollonii, Universiteit Gent

2008. You

can find it

here (full text).

In order to read it, you'll have to learn Dutch, but I guarantee you

that it's worth the effort! Both Philostratus'

Life of Apollonius

and his

Lives of the

Sophists are extensively discussed and contextualized in a

recent book by Adam M. Kemezis,

Greek

Narratives of the Roman Empire under the Severans: Cassius Dio,

Philostratus and Herodian (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press 2014). An article by

Gerard Boter about the title of

the

Life of Apollonius

appeared in the

Journal

of Hellenic Studies 135 (2015). In 2022 Boter's new

critical edition of the

Life

of Apollonius - the first one since Kayser's 1870

editio minor - has

been published in the series

Bibliotheca Teubneriana. A companion to this edition,

Critical Notes on Philostratus' Life of Apollonius of Tyana (Berlin/Boston 2023), has appeared in the series

Sammlung Wissenschaftlicher Commentare (

SWC). A lot of good information

on Apollonius of

Tyana can be

found on the internet, thanks to Jona Lendering, who has put online

Conybeare's 1912 Loeb translation

of Philostratus'

Life

of

Apollonius

as well as interesting articles on both

the author and the

main character.